Female single-parent family: a public policy issue

Família monoparental feminina: uma questão de política pública

DOI: 10.19135/revista.consinter.00019.04

Received/Recebido 31/03/2024 – Approved/Aprovado 25/06/2024

Marina Couto Giordano[1] – https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5597-0030

Alexandre Ventin de Carvalho[2] – https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4575-7707

Katia Maria Belisário[3] – https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1196-6148

Abstract

The traditional family unit consisting of a father, mother, and children no longer prevails in society as it did decades ago, giving way to other family structures such as the single-parent family, where only one person takes on the parenting role. This article aims to analyze the conditions for implementing public policies aimed at preventing or mitigating the impact of gender inequality in single-parent families led by women. The question guiding the research is what public policies can be effective in mitigating discrimination and unequal treatment given to female single-parent families. The starting point was a theoretical review of Brazilian single-parent families, the causes and impacts of gender inequalities, and public policies. The methodological process includes the SWOT matrix analysis (an acronym in English for the words strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) for diagnosing barriers to the implementation of suggested public policies. The hypothesis is that some social barriers make it difficult to implement public policies for single-parent families. The results show social barriers such as: lower income attainment; limited access to basic goods and services for members of single-parent families due to their low income; uncertain insertion into the job market; no proper family assistance; intensification of women’s double workload; school dropout; physical and psychological illness. Public policies are suggested based on the study.

Keywords: Female Single-Parent Families; Gender Inequality; Women; Public Policies.

Resumo

A família tradicional formada por pai, mãe e filhos já não permeia a sociedade como há algumas décadas e tem dado lugar a outros modelos de núcleos familiares, como a família monoparental, quando apenas uma pessoa assume a parentalidade da outra. O presente artigo tem como objetivo analisar as condições para a implementação de políticas públicas destinadas a prevenir ou mitigar o impacto da desigualdade de gênero em famílias monoparentais lideradas por mulheres. A pergunta que orienta a pesquisa é quais políticas públicas podem ser efetivas para mitigar a discriminação e o tratamento desigual dado às famílias monoparentais femininas. Partiu-se de uma revisão teórica sobre famílias brasileiras monoparentais, as causas e os impactos das desigualdades de gênero e políticas públicas. O processo metodológico inclui a análise matriz SWOT (acrônimo em inglês para as palavras forças, fraquezas, oportunidades e ameaças) para diagnóstico das barreiras à implementação das políticas públicas sugeridas. A hipótese é que algumas barreiras sociais dificultam a implementação de políticas públicas para famílias monoparentais. Os resultados mostram barreiras sociais como: desigualdade salarial; acesso limitado a bens e serviços básicos; inserção precária de filhos menores e de outros parentes no mercado de trabalho; menores sem a adequada assistência familiar; acirramento da dupla jornada feminina; evasão escolar; adoecimento físico e psíquico. Sugere-se políticas públicas com base no estudo.

Palavras-chave: Famílias Monoparentais Femininas; Desigualdade de Gênero; Mulheres; Políticas Públicas.

Summary: 1. Introduction. 2. Theoretical review. 2.1. Gender inequality: causes and impacts. 2.2. Public policies to aid female single-parent families. 3. SWOT Analysis. 3.1. Scenario Analysis: Strengths. 3.2. Scenario Analysis: Weaknesses. 3.3. Scenario Analysis: Opportunities. 3.4. Scenario Analysis: Threats. 3.5. Diagnosis. 4. Impacts of gender inequality and suggested public policies. 5. Final considerations. 6. References.

1 INTRODUCTION

The family constitutes the oldest social institution, predating even the legal organization of life in society itself, according to Machado and Voos (2022). This institution has undergone transformations over time, and Santana (2014) points out that the traditional family model consisting of a father, mother, and children no longer prevails in society as it did decades ago, giving way to other family models, such as the single-parent family, where only one person takes on the parenting role.

The purpose of this article is to analyze the conditions for the implementation of public policies aimed at preventing or mitigating the impact of gender inequality in single-parent families led by women. The question guiding the research is what public policies can be effective in mitigating discrimination and unequal treatment given to female single-parent families.

The hypothesis is that some social barriers make it difficult to implement public policies aimed to single-parent families. The starting point was a theoretical review of Brazilian single-parent families, the causes and impacts of gender inequalities, and public policies that assist female single-parent families. The methodological process consists of developing a SWOT matrix to analyze the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats that enable or act as barriers to the implementation of suggested public policies.

In fact, as result, we found out that social barriers make much more difficult to implement public policies to assist female single-parent families such as: lower income attainment; limited access to basic goods and services for members of single-parent families due to their low income; difficulties to insert into the job market; no proper family assistance; intensification of women’s double workload; school dropout; physical and psychological illness.

2 THEORETICAL REVIEW

According to Oliveira and Carvalho (2018), the single-parent family has always existed and primarily resulted from the widowhood of one of the spouses, extramarital relationships, or abandonment of the woman before or during marital cohabitation. However, it was in the 1960s that this family structure model gained greater visibility, considering the structural changes resulting from social and feminist movements, which culminated in Brazil with the enactment of Law No. 6,515, of December 26, 1977 (Divorce Law), making divorce another cause of the formation of a single-parent family.

The Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988 advanced on the topic. Article 226, paragraph 4, of the Constitution recognizes the single-parent family as a family entity by stating that “the community formed by any of the parents and their descendants is also understood as a family entity”. In this sense, it discusses the expansion of the concept of family entity:

The concept of family, previously restricted to those formed by marriage, was expanded to encompass the single-parent family. This type of family broke with the preconceived idea that the family nucleus must originate from marriage and include the father, mother, and children. The fact is that this family entity can originate from various factors and only comprise one of the parents and their descendants. Society finds itself confronted with the presence of both biparental and single-parent families side by side in everyday life (Santos; Santos, our translation[4]).

To the National Family Observatory (2021a), the percentage of single-parent families among the types of family composition – couples, single-parent families, and single-person households – is significant. Their participation was 18.5% in 2015, of which 16.3% correspond to female single-parent families and 2.2% correspond to male single-parent families. Based on the mentioned data, it is concluded that 86.6% of single-parent families are headed by women.

Feijó (2023) reveals that women heading single-parent families earn lower income when compared to married men with children and married women with children. According to the researcher, in 2022, the income of women heading single-parent families was 39% lower than the income of married men with children and 20% lower when compared to the income of married women with children.

This disparity is mainly related to two factors. The first one is linked to gender inequality in the Brazilian labor market, structured in the persistent wage gap between men and women in various sectors and occupational groups – a phenomenon referred to as "labor market discrimination", and in the concentration of women in occupations and sectors traditionally associated with the female sex – termed "occupational segregation" as Cotrim et al. (2020) point out.

According to Araújo and Ribeiro (2021), labor market discrimination occurs when, despite women having the same professional qualifications as men, they receive lower pay for performing the same activity, and/or receive lower pay for having access to lower-paying occupations. Occupational segregation, on the other hand, is characterized not only by the concentration of women in occupations and sectors associated with the female sex, but also by the fact that these occupations are lower-paid precisely because women are concentrated in performing such activities.

Another factor that contributes to the wage disparity between the income of women heading single-parent families and married men and women with children is related to the need for those women to seek occupations with flexible schedules, often resorting to informal employment. It is well known that informal positions are characterized by offering lower pay and lacking any form of social protection, as Feijó (2023) points out.

The Inter-Union Department of Statistics and Socioeconomic Studies – DIEESE (2023, p. 11) shows that out of the total black heads of households, 20.6% are informal domestic workers; 15.1% work informally; and 17.6% are self-employed without a National Register of Legal Entities (CNPJ). This means that more than half of these women do not have access to labor benefits (53.3%). Among non-black women, this proportion is 41.0%. Of these, 11.9% are informal domestic workers; 11.7% work informally; and 17.4% are self-employed without a CNPJ.

The insertion of black women into the labor market is even more challenging, and when they are employed, they earn less for the work performed. Feijó (2023) mentions in her study that black women heading single-parent families have an income 39.2% lower than that of single-parent families headed by women who self-identify as white or mixed-race. One of the reasons for this disparity, according to the researcher, is the level of education. Approximately 21% of white or Asian mothers have a college degree. This percentage drops to 9% among black or mixed-race mothers.

The numbers demonstrate the existence of a contingent of women who earn less and are precariously integrated into the labor market. According to DIEESE (2023), the difference in income reflects throughout the family, as it determines the possibility of access by its members to basic goods and services, the level of well-being of each one, sometimes imposing the precarious insertion of children and other relatives into the labor market to contribute to the income.

This scenario is exacerbated by the gender and race inequality so prevalent in our society, further complicating the insertion of women – especially black women – into the labor market. Discrimination is strongly related to social exclusion, which, in turn, is one of the factors that originates and reproduces poverty.

In Brazil, gender and race inequality in the labor market concerns the vast majority of the population, as women make up 43% of the economically active population, and blacks, of both genders, represent 46%. Black women, in turn, according to Abram (2006), account for 18% of the economically active population and face a disadvantaged situation in the main social and labor market indicators.

Despite the increase in the number of female single-parent families and the difficulties faced by family heads in solo parenting, there are no specific public policies aimed at supporting their autonomy, particularly financial autonomy.

The Brazilian Federal Constitution states:

It is the duty of the family, society, and the State to ensure, with absolute priority, to children, adolescents, and youth, the right to life, health, food, education, leisure, professional training, culture, dignity, respect, freedom, and family and community life, as well as to protect them from all forms of neglect, discrimination, exploitation, violence, cruelty, and oppression (Brazil, 1988, our translation[5]).

This challenge, to be shared by the entire society, is even greater for the head of a single-parent family, who must take on diverse roles within the household. By simultaneously fulfilling the roles of "father" and "mother", they must create, care for, provide for, and provide the affection that their dependents so greatly need.

In view of the constitutional precept, therefore, it is the duty of the State to stimulate social actions that benefit single-parent families, ensuring access to fundamental rights for their members. However, for this to materialize, it is necessary to provide the means to guarantee the effectiveness of such rights. The promotion of public policies is one of the mechanisms for this guarantee, with the Executive Branch playing a leading role in addressing demands of such complexity.

Although the duty to ensure the enjoyment of fundamental rights for children, adolescents, and youth is shared among family, society, and the State, it is still not possible to assert that such rights are respected in Brazil. When focusing on the reality of single-parent families, the situation is even more dire. Several factors contribute to the continued daily violation of fundamental rights within these families, with harmful consequences for both present and future society. Therefore, it is opportune to discuss ways to overcome this reality, starting with strategic planning of the necessary decisions.

2.1 Gender Inequality: Causes and Impacts

Gender inequality is a social phenomenon that has perpetuated in all societies worldwide. For several generations, women have held a position of submission and vulnerability to men, due to discrimination against the female gender, having been victims of different forms of violence and violations of fundamental rights, as refers Giancursi (2023).

In her work "The Second Sex", when assessing how women are socially perceived, Beauvoir (2009) creates the concept of the "Other", a category in which women are placed because they are not defined in themselves but in relation to men and through the male gaze. Thus, man is the "Subject", while woman is the "Other", the "invisible", the "inessential". Despite the equality between men and women in rights and obligations, as stipulated in Article 5, item I, of the Brazilian Federal Constitution, women still suffer from the impact caused by gender inequality. Therefore, the question arises: what are its causes?

A determining factor that directly influences gender inequality is patriarchy, which consists of a system of social relations in which male domination prevails. Giancursi (2023) emphasizes that the patriarchal model is based on the idea that men are superior to women and that their authority is natural and inevitable. This model manifests itself in different ways in different cultural contexts, leading to gender inequality in many areas of life. Zanello (2022) highlights that:

A reading of bodies, placing sexual difference as structural, therefore served to justify the distribution of spaces (public and private) and functions (caring for women and providing for men). Capitalism operated through the gendered division of labor, which was the way this oppression was carried out. What appears today as "natural" was historically and culturally shaped (Zanello, 2022, our translation[6]).

The oppression is bigger when we take into account sex, race and class.

Privileged feminists have largely been unable to, with, and for diverse groups of women because they either do not understand fully the interrelatedness of sex, race and class oppression or refuse to take this interrelatedness seriously” (hooks, 2000, p. 15).

Hooks also explains “as a group, black women are in an unusual position in this society, for not only are we collectively at the bottom of the occupational ladder, but our overall social status is lower than that of any other group” (hooks, 2000, p. 16).

Researcher and activist Judith Butler, just wrote a book named Who’s Afraid of Gender?, explains in her book, according to Finn Mackay (2024):

(...) ‘gender’ has become a phantasm, representing multiple human fears and anxieties about sexuality, bodily attributes, sex and relationships. These anxieties have been stoked and manipulated by rightwingers in positions of religious and secular power to more effectively project the harms they are complicit in onto women and minorities (Mackay, 2024).

In fact, religions sometimes end up playing an important role in maintaining patriarchy, as ideological discourse supports and legitimizes the imbalance between the sexes, reinforcing inequality with interpretations that reinforce gender stereotypes that can be observed, for example, in the myth of Adam and Eve (Fernandes, 2019).

Thus, patriarchy brings harm not only to women but to society as a whole. The consequences encompass both the public and private spheres, with notable examples being inequality in the labor market and violence against women, which structurally have more visibility and define various situations in the lives of the female population (Castro, Santos, Santos, 2018). But how does the gender inequality generated by patriarchal culture specifically impact single-parent families led by women?

One of the reflections of gender inequality is the lower income earned compared to married men with children and married women with children, according to Feijó (2023). This disparity is mainly related to two factors. The first is linked to gender inequality in the Brazilian labor market structured by the persistent wage gap between men and women in various sectors and occupational groups – a phenomenon called "labor market discrimination", and the concentration of women in occupations and sectors traditionally associated with the female sex – termed "occupational segregation", as explain Cotrim et al. (2020).

To Feijó (2023) the second factor that leads to lower income for single-parent family heads is related to the need for these women to seek occupations with flexible hours, often resorting to informal employment. It is well known that informal positions are characterized by offering lower remuneration and being devoid of any type of social protection.

The income difference reflects throughout the single-parent family, as it limits the possibility of access by its members to basic goods and services. Thus, the female single-parent family finds itself in a situation of vulnerability, as the woman does not have the financial means to cover household and children's expenses, facing difficulties in her own and her family's subsistence when experiencing single parenthood, according to Machado and Voos (2022).

This close relationship between poverty and female single parenthood, in turn, imposes the precarious insertion of minor children and other relatives into the labor market to contribute to the family income (DIEESE, 2023) or even the outsourcing of childcare – leaving children without proper family care and interaction – so that she can pursue her profession.

Another reflection of gender inequality that impacts female single-parent families is the intensification of the double workday. The overload of domestic and care work is exacerbated by the backward and persistent view that house and people care is a feminine issue, when it should be a responsibility taken on by everyone.

The intensification of the double workday is a barrier for these women to develop personally, with single-parent family heads being strong candidates for dropping out of school, as the need to work sometimes prevents them from continuing their studies or participating in training programs, as highlighted by Silva (2017).

It is also pointed out as a reflection of gender inequality the physical and psychological illness of these mothers due to constant concern about providing their children with basic subsistence conditions and exhaustion and isolation due to the absence of a support network.

In this context of inequality and women’s illness:

The main question is how to negotiate gender discourse and construct meaning. This negotiation, present in social networks, is not as clear in newspaper news, despite activism in blogs and female columns and some legislative advances. A patriarchal and hegemonic discourse still predominates [...] It is necessary, first of all, to touch the wound, deepen the political, corporate, and life implications of the women and children involved, and finally, implement public policies to support victims and educate for the prevention of such violence (Belisário; Mendes, 2019, our translation[7]).

2.2 Public Policies to Aid Female Single Parent Families

Before discussing the need to develop public policies that can assist the needs of female single-parent families, it is necessary to conceptualize what public policy means:

(...) the set of guidelines and interventions emanating from the State, carried out by individuals and legal entities, both public and/or private, with the aim of addressing public issues that require, use, or affect public resources (Brasil, 2021, our translation[8]).

According to Secchi (2013), public policy is a guideline formulated to address a public issue; in other words, the reason for establishing a public policy is the treatment or resolution of a problem understood as collectively relevant.

The National School of Public Administration (2007, pp. 28-29) defines public policy as:

(…) a flow of public decisions, aimed at maintaining social equilibrium or introducing imbalances intended to modify this reality, whose purpose is to maintain or modify the reality of one or several sectors of social life, through the definition of objectives and strategies of action and the allocation of resources necessary to achieve the established objectives (our translation[9]).

Based on the mentioned concepts, it is observed that a public policy has two fundamental elements, namely: public intentionality and a response to a public problem. Thus, the reason for establishing a public policy is the treatment or resolution of a problem understood as collectively relevant as highlighted Secchi (2013).

As mentioned, there are no public policies specifically targeted at female single-parent families. This family structure may be in a vulnerable state, as the majority of women heading these families do not have the financial means to cover the basic expenses of the household and their children, due to difficulties in their integration into the labor market – marked by gender and race inequalities – which intensifies and perpetuates this state of vulnerability, explain Machado and Voos (2022).

In response to the need for the development of public policies on the topic, Senator Eduardo Braga introduced Bill No. 3,717 of 2021 (Brasil, 2021b), which provides "for the priority of single mothers in accessing public policies that promote the human capital formation of themselves or their dependents, including in the areas of labor market, social assistance, childcare, housing, and mobility – at the federal, state, district, or municipal level" (art. 1st, heading). Therefore, the Bill prioritizes access for single mothers to public policies in the listed areas, across all four levels of government.

The proposal also stipulates that public policies concerning job intermediation and professional qualification will aim to promote the insertion of single mothers into the labor market and combat gender wage inequality, offering priority assistance to these women and providing services in areas with higher potential for income and professional growth (art. 6).

Additionally, among the proposed measures are the doubling of social assistance benefits for families with children and adolescents (art. 4); priority in daycare centers (arts. 13 and 14); special time regime with greater flexibility for reducing working hours and using a time bank (art. 9); hiring quotas (art. 9); extension of maternity leave for up to 180 days (art. 10); and subsidies for urban transportation (arts. 17 and 18).

The proposed measures are aimed at the single-parent female head of household registered in the Unified Registry for Social Programs and with dependents up to 18 years of age (art. 3, introduction). The Bill was approved in the Federal Senate and is currently under analysis in the House of Representatives. If approved, the law will be in force for 20 years, or until the poverty rate in households headed by single-parent females is reduced to 20% (art. 2, introduction).

Although Bill No. 3,717 of 2021 represents progress in ensuring rights for single-parent female-headed households, indicating pathways for public policies in important areas of this family model, the mentioned bill does not encompass the complexity of issues related to the topic, especially concerning psychological support for these women and/or their dependents.

With the aim of improving public policies so that they achieve their objectives efficiently and effectively, truly serving the interests of citizens, the Federal Court of Accounts published a booklet entitled “Public Policy in Ten Steps”. This is a practical guide aimed at public managers, compiling national and international best practices in the development, implementation, and monitoring of results of a public policy (Brasil, 2021c)

Picture 1 – Public Policy in Ten Steps

Source: adapted from Federal Court of Accounts (Brasil, 2021c, pp. 12-31).

The mentioned publication highlights the importance of the public policy formulation process, as well as the evaluation of the impact of its implementation, so that the results are satisfactory. Otherwise, the path to be pursued by the public manager may result in exacerbating the crisis of confidence already so associated with the Executive Branch, due to its inability to solve public problems.

3 SWOT ANALYSIS

With the aim of analyzing the conditions for strategic decision-making regarding the implementation of the public policies listed in the fourth part of this article, the SWOT matrix was used.

Created by Harvard Business School professors Kenneth Andrews and Roland Christensen in the 1950s, this tool is directly linked to strategic planning and is one of the most well-known concepts of the design school. In general terms, Mintzberg; Ahlstrand; Lampel, (2000) proposes a strategy formulation model that aims to achieve a fit between internal capabilities – strengths and weaknesses – and external possibilities – opportunities and threats – of an organization.

Through mapping internal strengths and weaknesses and external opportunities and threats, the SWOT analysis is an important tool for those responsible for creating strategies have the necessary insights to make the most of opportunities and strengths, while minimizing or even eliminating weaknesses and threats that hinder the organization from thriving as Dutra (2014) explains.

Variables of strength and weakness are used for the analysis of the internal environment. Strengths are the internal variables that provide favorable conditions influencing the organization's performance positively. Weaknesses are the deficiencies that hinder the organization's performance capacity. These variables can be controlled by the organization according to Souza e Souza et al. (2017).

Variables of opportunity and threat are used for the external environment. Opportunities are external situations capable of contributing to the achievement of strategic objectives that can create favorable conditions for the organization. Threats are external situations that can hinder the execution of strategic objectives, directly impacting the organization. Both variables cannot be controlled by the organization, as Souza e Souza et al. (2017) argues.

3.1 Scenario Analysis: Strengths

The state's ability to implement public policies, the inequality indicators created by research institutes, and the existing public policies are listed as strengths.

The planning, creation, and execution of public policies are the result of joint efforts by the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial branches – at the federal, state, and municipal levels, with the first two being responsible for proposing them. This capacity of the state to implement public policies can be considered a strength, as they are tools belonging to the government itself for making progressive changes in society, ensuring that citizens enjoy the rights guaranteed by law, according to Miguel (2018).

Another strength identified consists of the existence of inequality indicators. Indicators, in public management, are instruments capable of identifying and measuring aspects related to a certain phenomenon resulting from the action or omission of the state. The main purpose of the indicator is to translate, in a measurable way, an aspect of the given or constructed reality, in order to operationalize its observation and evaluation, as highlighted by Bahia, (2021).

Therefore, indicators capable of measuring income differentials among races and genders, as well as among various types of family units, are examples of important instruments that lead to the monitoring and eventually the improvement of a public policy. In this sense:

Management by indicators is based on the principle formulated by James Harrington: measuring is the first step that leads to control and eventually to improvement. If you don't understand it, you can't control it. If you can't control it, you can't improve it (Bahia, 2021, our translation[10]).

Existing public policies can also be considered a strength, as they indicate paths in vital sectors of a female-headed single-parent family, with actions focused on education, health, housing, food security, and social assistance.

3.2 Scenario Analysis: Weaknesses

Bureaucracy, the slowness of the State, the non-use of indicators, the lack of planning and the level of training of public agents are considered weaknesses. It is the responsibility of the State to create and promote social actions that benefit single-parent families as a way to contribute to the well-being of the family, ensuring access to fundamental rights for the members of these families. However, the state response to this demand is insufficient, attributing this fact to bureaucracy and the slowness of the State.

To Santana (2014), the absence of public policies directly aimed at female single-parent families is a reflection of this bureaucracy and slowness of the State in meeting social demands, despite the growth of this family model, considering the structural changes resulting from social and feminist movements, which culminated in Brazil with the promulgation of Law No. 6,515, of December 26, 1977, entitled the Divorce Law.

Another weakness identified in this study is the non-utilization of indicators that enable the establishment of goals and the monitoring of results for conducting a critical analysis regarding the effectiveness of the creation of a specific public policy, for decision-making, and for the new planning cycle.

The lack of planning in the development of public policies is considered a weakness. Before formulating any public policy, it is necessary to conduct structured studies and analyses to determine whether the chosen alternative is the most advantageous when compared to other solution alternatives. Planning can also help diminish risks in the implementation of public policy and even prevent negative impacts from arising as a result of its implementation (Brasil, 2021c).

The level of training of public agents is identified as a weakness. The implementation of a public policy is carried out by people, who are crucial to ensuring that public policies are realized and that public services maintain quality.

3.3 Scenario Analysis: Opportunities

Social awareness about the role of women, advancements in legislation protective of women and families, civil society participation in the fight for women's rights, and a guaranteeing Judicial Branch are considered opportunities.

The increasing social awareness of the relevance of women's roles is considered an opportunity. Women are taking on new roles, occupying positions in the job market and leadership positions, despite the patriarchy affecting society.

The advancement in legislation protective of women and families is considered another opportunity. This progress is largely due to the feminist movement, which advocates for social, political, and economic equality between genders. These achievements strengthen the movement and create a more favorable environment for the advancement of the feminist goals.

In this sense, the struggle driven by civil society organizations emerges as strategic for the advancement of these goals. The existence of social movements and non-governmental institutions is crucial to mitigate the impact of social issues related to women and for the increasing awareness of the significant role played by women in society.

Furthermore, a guaranteeing and democratic Judiciary is considered an opportunity, as it does not compromise in the face of violations of fundamental rights and constitutional integrity, even in the presence of potential pressures from reactionary groups or ideologies.

3.4 Scenario Analysis: Threats

The culture of chauvinism and patriarchy; economic instability; low level of education among women; double workload (work/home/children); higher unemployment among women; inequality based on race and social class; and lower salaries compared to men are considered threats.

The culture chauvinism and of patriarchy is at the core of gender inequality that impacts various areas such as social, economic, political, and power, and “functions as an almost automatic mechanism, as it can be activated by anyone, including women” (Saffioti, 2015, p. 108). Thus, chauvinism and patriarchy are identified in this study as a barrier to the creation of the aforementioned public policies, as despite advancements, it still affects the State, which in turn produces policies of domination, subordination, and exploitation of women, affecting the entire society, points out Brambilla (2020).

Economic instability is identified as a threat, as there are financial costs associated with the implementation of public policies. Thus, any economic crisis, such as the one that has affected the country due to COVID-19, can hinder the implementation of proposed actions aimed at achieving the goals and objectives of public policies.

Low level of education is another identified threat that also can hinder the implementation of public policies specially created to stimulate the entry of women in the labor market. Feijó (2023) reveals that more than half of women heading single-parent families (54.3%) have completed the elementary school and less the 14% have university education. The low qualification of those women works as a barrier to better jobs.

The capacity of those women to seek more qualification and therefore to have more opportunities to progress in their careers get even worse due to the double workload, also identified as a threat for implementation of public policies. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE),[11] in 2019, 146.7 million persons aged 14 and over performed household chores. This number was equivalent to 85.7% of this population. The percentage of women responsible for these tasks (92.1%) is higher than that of men (78.6%).

According to the IBGE’s trimestral Continuous National Household Sample Survey – PNAD Continuous[12], at the end of 2023, the unemployment rate among women remained above the national average. All over the country, if considered the gender distinction, the unemployment rate in the fourth quarter of 2023 was equivalent to 7.4% of the economically active population. Considering gender, the unemployment rate among men was 6%, and among woman reached 9.2%[13].

Considering color or race, the unemployment rate for whites (5.9%), as well as for men, was lower than the national average. On the other hand, black (8.9%) and brown (8.5%) exceeded the average[14].

Continuous PNAD also revealed that the unemployment rate also changes due to the instruction levels. The unemployment rate is 3.6% for those who had complete higher education and for those who had incomplete secondary education the rate increases to 13%[15].

As a higher level of education is considered an aspect that provides virtuous effects, as in addition to increasing the productivity of the economy, it allows a lower unemployment rate and an improvement in wages, the development of public policies for female single-parent families, led by black or brown women, faces barriers precisely due to their lower availability for study, impacting their level of education and, consequently, their ability to remain economically employed and earn a higher income.

In 2010, the proportion of women, black or brown, with complete higher education corresponded to only 6.72% of the Brazilian population.[16] According to Delboni the education rate and gender are among the three main factors (together with the formalization of work) that impact in the wage gap:

For all analyzed sector, the results obtained in estimations at national level indicate that individual with more years of education receive higher income from their main job than individuals with fewer years of studies, as well as those who have a formal employment contract and are male. The return for each additional year of study was 7.5%, while having a work card added up to 77.7% to the income derived form the main job, depending on the sector in which the worker was inserted. Still according to the estimation results, male individual received at least 44.7% more when compared to females and this difference can be observed in all regions and sectors analyzed (Delboni, 2023, our translation[17]).

The 53.3% difference between unemployment rates of men and women, as well as the lower income historically earned by women, highlight the challenge that public policies will face. After all, women who lead single-parent families tend to have less availability to study due to the exhaustive dedication they give to family and work and, consequently, face a spiral that prevents them from reaching better jobs and increasing their income. Even the implementation of initiatives that aim to overcome such barriers tends to be difficult to implement, unless protective measures are ensured that allow women to share the burden of raising their children with the State.

This spiral, by reducing the availability of job offers (as a result of less time available) leads to a greater propensity to accept informal jobs (which tend to have greater flexibility in working hours), which, on the other hand, usually results in a higher level of employment and lower wages, which amplify social inequality, with more direct impacts on women who lead single-parent families. There are also problems related to housing and mobility, as some of these women tend to work in places far from their homes, as the lack of income pushes them to the suburbs, while opportunities in the job market are more concentrated in central locations.

There are challenges in the construction of public policies aimed at such families, therefore, overcoming the barriers imposed in the labor market, in early childhood education, in the limited social assistance provided by the State, in housing, urban mobility and in patriarchy that still legitimize behaviors that reduce women's space in the construction of society and which even make it difficult to create specific policies to overcome this state of vulnerability.

3.5 Diagnosis

As a consequence of the categorization and analysis described in subsections 3.1 to 3.4, the positive and negative factors – whether they are of exogenous or endogenous origin to the state itself – impacting the construction of public policies for female single-parent families have been synthesized in Table 1, structured in the form of a SWOT matrix.

Table 1 – SWOT Analysis

|

|

POSITIVE FACTORS |

NEGATIVE FACTORS |

|

INTERNAL FACTORS |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

- State’s ability to implement public policies - inequality indicators created by research institutes - existing public policies |

- bureaucracy - slowness of the State - non-use of indicators - lack of planning - level of training of public agents |

|

|

EXTERNAL FACTORS |

Opportunities |

Threats |

|

- social awareness about the role of women - advancements in legislation protective of women and families - civil society participation in the fight for women's rights - guaranteeing Judicial Branch |

- chauvinism and patriarchal culture - economic instability - low level of education among women - double workload (work/home/children) - higher unemployment among women - inequality based on race and social class - lower salaries compared to men |

Source: developed by the authors (2024).

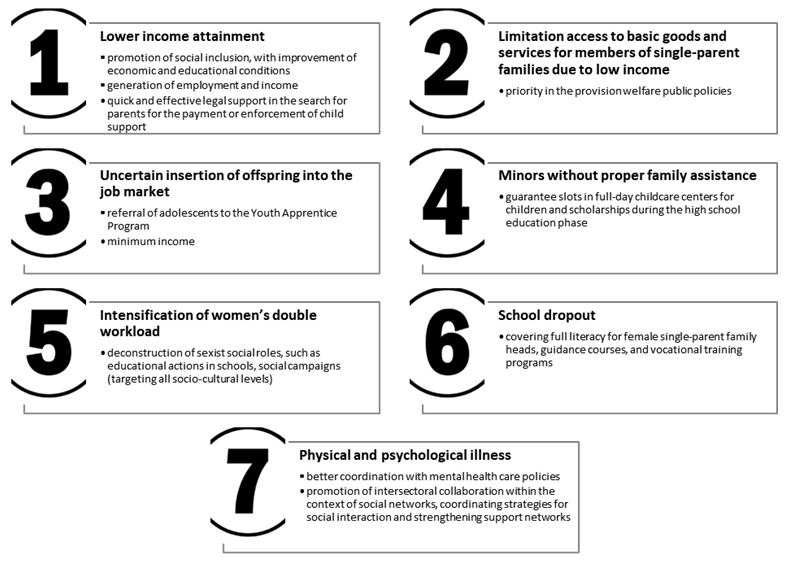

4 IMPACTS OF GENDER INEQUALITY AND SUGGESTED PUBLIC POLICIES

Gender inequality has a huge impact in all women’s life. However, for female single-parent families the impact is even more profound. Based on literature analysis, the main impacts of gender inequality were identified and for each one was suggested public policies aiming to reduce the challenges that the women heading single-parent families must overcome daily.

These are the research findings: lower income attainment; limitation access to basic goods and services for members of single-parent families due to low income; uncertain insertion of offspring into the job market; minors without proper family assistance; intensification of women’s double workload; school dropout; physical and psychological illness.

Based on the research findings described above, public policies capable of preventing or mitigating the impact of gender inequality in single-parent families led by women were suggested. Below is a picture summarizing the research findings and their correlation with prevention policies:

Picture 2 – Correlation between the impacts of gender inequality in female single-parent families and suggested public policies

Source: developed by the authors (2024).

5 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

To the head of a single-parent family falls the need to take on diverse roles within the household, simultaneously playing the roles of both "father" and "mother," and should create, care for, provide sustenance, and offer the affection that their dependents so greatly need.

In Brazil, 86.6% of single-parent families are headed by women. The data reveals that these women earn less and have precarious job market insertion. This scenario is exacerbated by the gender and racial inequality so prevalent in our society.

It is therefore the responsibility of the State to stimulate social actions that benefit single-parent families as a means of contributing to family well-being, ensuring access to fundamental rights for members of these families. It is necessary to create means to guarantee the effectiveness of such rights. The promotion of public policies is one of the mechanisms for their guarantee, with the Executive Branch playing a leading role in addressing demands of such complexity.

Even though there are no public policies directly aimed at single-parent families led by women, by identifying relevant factors that impact the spectrum of protection intended for the family unit and, especially, the interests of minors, it is possible to enumerate existing policies that could be used as means to mitigate or eliminate the unequal reality experienced by women, heads of households.

The question guiding the present study is what public policies can be effective in mitigating discrimination and unequal treatment given to female single-parent families. The methodological process includes the SWOT matrix analysis (an acronym in English for the words strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) for diagnosing barriers to the implementation of suggested public policies.

The guidance identified from internal and external factors reveals the need for the State to advance with policies aimed at specifically reaching women who are heads of single-parent families, ensuring survival strategies aimed at improving their living conditions and those of their families.

We observed many barriers to implement public policies for single-parent families such as: lower income attainment; limited access to basic goods and services for members of single-parent families due to their low income; difficulties to insert into the job market; no proper family assistance; intensification of women’s double workload; school dropout; physical and psychological illness.

The identification of existing public policies or the proposal of new ones, once the need is identified, as well as the evaluation of the impact of their implementation, is important to obtain and measure satisfactory results. Otherwise, the path to be pursued by the public manager may result in exacerbating the crisis of confidence already so associated with the Executive Branch, due to its inability to solve public problems.

Regarding the response to the research question about which public policies can be effective in mitigating inequalities and prejudices in single-parent families, it can be affirmed that any policy created to address the needs of women must always take into consideration social inclusion, income disparities, race, education, and working and health conditions of Brazilian women.

6 REFERENCES

ABRAM, Laís, “Desigualdades de gênero e raça no mercado de trabalho brasileiro”, Ciência e Cultura, vol. 58, dec. 2006, pp. 40-41, Available in: <http://cienciaecultura.bvs. br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0009-67252006000400020&lng=en&nrm=iso>, Access in: September 10, 2023.

ARAÚJO, Verônica Fagundes, RIBEIRO, Eduardo Pontual, “Diferenciais de salários por gênero no Brasil: uma análise regional”, Revista Econômica do Nordeste, vol. 33, pp. 196-217, Available in: <https://www.ufrgs.br/ppge/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2001-11.pdf>, Access in: September 4, 2023.

BAHIA, Leandro Oliveira, Guia referencial para construção e análise de indicadores, Brasília, Enap, 2021, Available in: <https://repositorio.enap.gov.br/bitstream/1/6154/1/ GR%20Construindo%20e%20Analisando%20Indicadores%20-%20Final.pdf>, Access in: October 1, 2023.

BEAUVOIR, Simone de, O segundo sexo, Rio de Janeiro, Nova Fronteira, 2009.

BELISÁRIO, Katia; MENDES, Kaithlynn, “Mídia e Violência Doméstica: a cobertura jornalística dos crimes de violência doméstica no Brasil e no Reino Unido” in Belisário, Katia et al., orgs, Gênero em Pauta: desconstruindo violências, construindo novos caminhos, Curitiba, Appris, 2019.

BRAMBILLA, Beatriz Borges, “Estado patriarcal e políticas para mulheres: da luta pela equidade de gênero ao caso de polícia”, Boletim de Conjuntura, vol. 5, n. 13, dez. 2020, pp. 27–42, 2020.

BRASIL, “Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil”, Available in: <https://www. planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

BRASIL, “Fatos e Números: Arranjos Familiares no Brasil”, Ministério da Mulher, da Família e dos Direitos Humanos, Observatório Nacional da Família, Secretaria Nacional da Família, Brasília, 2021, Available in: <https://www.gov.br/mdh/pt-br/navegue-por-temas/observatorio-nacional-da-familia/fatos-e-numeros/ArranjosFamiliares.pdf>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

BRASIL, “Projeto de Lei 3.717 de 2021”, Available in:<https://www.camara.leg.br/proposi coesWeb/prop_mostrarintegra?codteor=2147095>, Access in: September 10, 2022.

BRASIL, “Política pública em dez passos”, Tribunal de Contas da União, 2021, Available in: <https://portal.tcu.gov.br/data/files/1E/D0/D4/DF/12F99710D5C6CE87F1881 8A8/Politica%20Publica%20em%20Dez%20Passos_web.pdf>, Access in: September 10, 2023.

CASTRO, Ana Beatriz Cândido, SANTOS, Jakciane Simões dos, SANTOS, Jássira Simões

dos, “Gênero, patriarcado, divisão sexual do trabalho e a força de trabalho feminina na sociabilidade capitalista”, VI Seminário CETROS – Crise e mundo do trabalho no Brasil, Available in: <https://www.uece.br/eventos/seminariocetros/anais/trabalhos_completos/425-51197-29062018-084053.pdf>, Access in: October 4, 2023.

CONSINTER – CONSELHO INTERNACIONAL DE ESTUDOS CONTEMPORÂNEOS EM PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO, “Edital para submissão de artigos revista internacional Consinter de Direito e Livro Direito e Justiça”, Available in: https://consinter.org/edital; Access in: June 16, 2024.

COTRIM, Luisa Rabioglio, TEIXEIRA, Marilane Oliveira, PRONI, Marcelo Weushaupt, “Desigualdade de gênero no mercado de trabalho formal no Brasil”, Texto para discussão, n. 383, jun. 2020. pp. 1-28, Available in: <https://observatorio2030.com.br/wp-content/ uploads/2022/03/Desigualdade-de-genero-no-mercado-de-trabalho-formal-no-Brasil.pdf>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

DELBONI, Maria Gertrudes Posmoser, Desigualdade de Rendimentos no Brasil: uma decomposição a partir da PNADC, Masters thesis (Master in Economics), Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, 2023, Available in: <https://sappg.ufes.br/tese_drupal//tese_ 15255_Dissert_final%20-%20Maria%20Gertrudes%20Posmoser%20Delboni.pdf >, Access in: March 30, 2024.

DIEESE – DEPARTAMENTO INTERSINDICAL DE ESTATÍSTICA E ESTUDOS SÓCIOECONÔMICOS, “As dificuldades das mulheres chefes de família no mercado de trabalho”, Boletim Especial 8 de março Dia da Mulher, mar. 2023, Available in: <https://www.dieese.org.br/ boletimespecial/2023/mulheres2023.pdf>, Access in: September 9, 2023.

DUTRA, Daniele Vasques et al., “A análise SWOT no Brand DNA Process: um estudo da

ferramenta para aplicação em trabalhos em Branding”, 2014, 241, Masters thesis (Master in Design), Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2014, Available in: <https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/128970>, Access in: October 1, 2023.

FEIJÓ, Janaína, “Mães solo no mercado de trabalho crescem 1,7 milhão em 10 anos”, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 2023, Available in: <https://portal.fgv.br/artigos/maes-solo-mercado-trabalho-crescem-17-milhao-dez-anos>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

FERNANDES, Isabela Vince Esgalha, “Gênero, Igreja e dominação”, Revista Gênero &Direito, v. 8, n. 3, 2019, pp. 25-40.

GIANCURSI, Mariana Baldo, “Violência obstétrica: uma das espécies de violências contra as mulheres”, II Fórum de Direito Internacional e Direitos Humanos, 2023, Available in: <http://intertemas.toledoprudente.edu.br/index.php/didh/article/view/9595>, Access in: October 2, 2023.

GIUBERTI, Ana Carolina, MENEZES-FILHO, Naércio, “Discriminação de rendimentos por gênero: uma comparação entre o Brasil e os Estados Unidos”, Economia Aplicada, Ribeirão Preto, v. 9, n. 3, pp. 369-384, jul./set. 2005, Available in: <https://www.scielo.br/j/ecoa/a/ 6WCSZdT5GWYs7DmSKcSpGYv/#:~:text=No%20Brasil%2C%20as%20caracter%C3%ADsticas%20das,parte%20do%20diferencial%20de%20sal%C3%A1rios>, Access in: September 10, 2023.

IBGE – INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA, “Em média, mulheres dedicam 10,4 horas por semana a mais que os homens aos afazeres domésticos ou ao cuidado de pessoas”, Rio de Janeiro, IBGE, 2020, Available in: <https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-sala-de-imprensa/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/27877-em-media-mulheres-dedicam-10-4-horas-por-semana-a-mais-que-os-homens-aos-afazeres-domesticos-ou-ao-cuidado-de-pessoas#:~:text=Em%202019%2C%20146%2C7%20milh%C3%B5es,homens%20(78%2C6%25).>, Access in: March 31, 2024.

IBGE – INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA, “PNAD Contínua – Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua”, Rio de Janeiro, IBGE, 2023, Available in: <https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/trabalho/9173-pesquisa-nacional-por-amostra-de-domicilios-continua-trimestral.html?=&t=resultados>, Access in: March 30, 2024.

IBGE – INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA, “PNAD Contínua Trimestral: desocupação recua em duas UFs no 4º trimestre de 2023”, Rio de Janeiro, IBGE, 2024, Available in: <https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-sala-de-imprensa/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/39205-pnad-continua-trimestral-desocupacao-recua-em-duas-ufs-no-4-trimestre-de-2023>, Access in: March 30, 2024.

MACHADO, Milena Furghestti, VOOS, Charles Henrique, “A família monoparental feminina e a necessidade de políticas públicas específicas”, Monumenta – Revista de Estudos Interdisciplinares, v. 3, n. 6, jul./dez., 2022, pp. 126-151.

MACKAY, Finn, “Who’s Afraid of Gender? by Judith Butler review – the gender theorist goes mainstream”, The Guardian, 13 mar. 2024, Available in: <https://www.theguardian.com/ books/2024/mar/13/whos-afraid-of-gender-by-judith-butler-review-the-gender-theorist-goes-mainstream>, Access in: March 28, 2024.

MIGUEL, Lailane Lima, “A Lei de Responsabilidade Fiscal e a Implementação das Políticas Públicas”, Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento, ed. 7, vol. 4, jul. 2018, pp. 80-94.

MINTZBERG, Henry, AHLSTRAND, Bruce, LAMPEL, Joseph, Safári de estratégia: um roteiro para selva do Planejamento Estratégico, Porto Alegre, Bookman, 2000.

OLIVEIRA, Antonia Ruana Barbosa de, CARVALHO, Luciene Ferreira Mendes de, “Família monoparental feminina e pobreza: uma abordagem histórica e social”, Praia Vermelha, v. 28, n. 1, 2018, pp. 337-355, Available in: <https://revistas.ufrj.br/index.php/praiavermelha/ article/view/12748/13418>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

SAFFIOTI, Heleieth, Gênero, Patriarcado, Violência, ed. 2, São Paulo, Fundação Perseu Abrahmo, 2015.

SANTANA, Edith Licia Ferreira Felisberto, “Família monoparental feminina: fenômeno da contemporaneidade?”, Polêm!ca – Revista Eletrônica, v. 13, n. 2, abr./jun. 2014, pp. 1225-1236, Available in: <https://revistajuridica.presidencia.gov.br/ index.php/saj/article/download/209/198/433>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

SANTOS, Jonábio Barbosa dos, SANTOS, Morgana Sales da Costa, “Família monoparental brasileira”, Revista Jurídica, v. 10, n. 92, out. 2008/jan. 2009, pp. 1-30, Available in: <https://revistajuridica.presidencia.gov.br/index.php/saj>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

SECCHI, Leonardo, Políticas Públicas – conceitos, esquemas de análise, casos práticos, 2. ed. São Paulo, CENPAGE, 2013.

SILVA, Simone Tavares da, “Perspectivas da vida das mulheres chefes de família: sonhos e utopias”, VIII Jornada Internacional Políticas Públicas, ago. 2017, Available in: <https://www.joinpp.ufma.br/jornadas/joinpp2017/pdfs/eixo6/perspectivasdevidadasmulhereschefesdefamiliasonhoseutopias.pdf>, Access in: October 5, 2023.

SOUZA E SOUZA, Luís Paulo et al., “Matriz swot como ferramenta de gestão para melhoria da assistência de enfermagem: estudo de caso em um hospital de ensino”, Revista Eletrônica Gestão & Saúde, vol. 4, n. 1, ago. 2017, pp. 1633–1643, Available in: <https://periodicos.unb. br/index.php/rgs/article/view/207>, Access in: October 1, 2023.

ZANELLO, Valeska: A Prateleira do Amor, Curitiba, Appris, 2022.

[1] PhD candidate in Constitutional Law at the Brazilian Institute of Teaching, Development, and Research (IDP), Postal Code 70200-670, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil, email giordano_marina@yahoo.com. ORCID https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5597-0030

[2] PhD candidate in Constitutional Law at the Brazilian Institute of Teaching, Development, and Research (IDP), Postal Code 70200-670, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil, email aventin@terra.com.br. ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4575-7707

[3] Associate Professor at the Faculty of Communication at the University of Brasília (UnB) and the Graduate Program in Human Rights PPGDH. She holds a PhD in Journalism and Society from UnB and completed post-doctoral internships at the Media, Communication and Sociology Department, University of Leicester, United Kingdom (2017/2018), and at the Graduate Program in Communication and Consumption Practices of the School of Advertising and Marketing (2020). Postal Code 70910-900, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil, email katia.belisario@gmail.com. ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1196-6148

[4] SANTOS, Jonábio Barbosa dos; SANTOS, Morgana Sales da Costa, “Família monoparental brasileira”, Revista Jurídica, v. 10, n. 92, out. 2008/jan.2009, p. 20, Available in: <https://revistajuridica.presidencia.gov.br/index.php/saj>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

[5] BRASIL, Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil, art. 227, Available in: <https://www. planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

[6] ZANELLO, Valeska: A Prateleira do Amor, Curitiba, Appris, 2022, p. 37.

[7] BELISÁRIO, Katia; MENDES, Kaithlynn, “Mídia e Violência Doméstica: a cobertura jornalística dos crimes de violência doméstica no Brasil e no Reino Unido”, in Belisário, Katia et al., orgs, Gênero em Pauta: desconstruindo violências, construindo novos caminhos, Curitiba, Appris, 2019, p. 49.

[8] BRASIL, “Fatos e Números: Arranjos Familiares no Brasil”, Ministério da Mulher, da Família e dos Direitos Humanos, Observatório Nacional da Família, Secretaria Nacional da Família, Brasília, 2021, p.10, Available in: <https://www.gov.br/mdh/pt-br/navegue-por-temas/observatorio-nacional-da-familia/fatos-e-numeros/ArranjosFamiliares.pdf>, Access in: September 3, 2023.

[9] BRASIL, “Projeto de Lei 3.717 de 2021”, Available in:<https://www.camara.leg.br/proposi coesWeb/prop_mostrarintegra?codteor=2147095>, Access in: September 10, 2022.

[10] BAHIA, Leandro Oliveira, Guia referencial para construção e análise de indicadores, Brasília, Enap, 2021, p. 12, Available in: <https://repositorio.enap.gov.br/bitstream/1/6154/1/ GR%20Construindo%20e%20Analisando%20Indicadores%20-%20Final.pdf>, Access in: October 1, 2023.

[11] IBGE, “Em média, mulheres dedicam 10,4 horas por semana a mais que os homens aos afazeres domésticos ou ao cuidado de pessoas”, Rio de Janeiro, IBGE, 2020, Available in: <https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-sala-de-imprensa/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/27877-em-media-mulheres-dedicam-10-4-horas-por-semana-a-mais-que-os-homens-aos-afazeres-domesticos-ou-ao-cuidado-de-pessoas#:~:text=Em%202019%2C%20146%2C7%20milh%C3%B5es,homens%20(78%2C6%25).>, Access in: March 31, 2024.

[12] IBGE, “PNAD Contínua – Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua”, Rio de Janeiro, IBGE, 2023, Available in: <https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/trabalho/9173-pesquisa-nacional-por-amostra-de-domicilios-continua-trimestral.html?=&t=resultados>, Access in: March 30, 2024.

[13] IBGE, “PNAD Contínua Trimestral: desocupação recua em duas UFs no 4º trimestre de 2023”, Rio de Janeiro, IBGE, 2024, Available in: <https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-sala-de-imprensa/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/39205-pnad-continua-trimestral-desocupacao-recua-em-duas-ufs-no-4-trimestre-de-2023>, Access in: March 30, 2024.

[14] IBGE PNAD, 2023, Available in: <https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-sala-de-imprensa/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/39205-pnad-continua-trimestral-desocupacao-recua-em-duas-ufs-no-4-trimestre-de-2023>, Access in: March 30, 2024.

[15] Ibidem.

[16] Ibidem.

[17] DELBONI, Maria Gertrudes Posmoser, Desigualdade de Rendimentos no Brasil: uma decomposição a partir da PNADC, Masters thesis (Master in Economics), Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, 2023, p. 47, Available in: <https://sappg.ufes.br/tese_drupal//tese_ 15255_Dissert_final%20-%20Maria%20Gertrudes%20Posmoser%20Delboni.pdf >, Access in: March 30, 2024.