Of the Brazilian Supreme Court in the Right to Health: Symbolic or Effective?

Fernando Rister de Sousa Lima[1]

Resumo: A pesquisa tem como objetivo identificar se o desempenho do Supremo Tribunal Federal (STF) sobre o direito à saúde resulta em eficácia ou em simbolismo. O estudo foi feito por meio de uma pesquisa teórica e investigação empírica. A coleta de dados concentrou-se em sociologia teórica, dando destaque ao livro “Teoria de Sistemas”, de Niklas Luhmann, que foi usado na identificação da racionalidade legal, inclusão social, complexidade, contingência, justiça, e funções dos Tribunais, do Sistema Político e do Sistema Legal. Na referência teórica, a conceptualização da expressão: “simbólico” é extremamente rica, ao ponto de encontrar-se uma rotineira confusão semântica; para evitá-la, este trabalho abrange a tese desenvolvida por Marcelo Neves em seu livro: A Constitucionalização Simbólica, no qual ele desenvolve um debate sobre o simbolismo de normas constitucionais. Para a pesquisa empírica, pelos métodos de pesquisa, fez-se uma investigação documental, coletada dos principais precedentes do Supremo Tribunal Brasileiro. O resultado da pesquisa compôs um paradoxo. Descobriu-se que o Supremo Tribunal Federal, em um ponto de vista restrito aos litigantes, procura uma eficácia ilusória do direito à saúde, que é simbólica, tanto quanto o juiz de uma racionalidade exclusiva adjudicatória, negando-se, consequentemente, a ver a questão como distributiva, como um problema de distribuição de riqueza, que, em uma macro perspectiva, causa o risco de corrupção no sistema político para forçar a administração pública a distribuir uma riqueza que às vezes nem mesmo existe, e também exclui a maior parte da população, que não tem acesso a este Tribunal ou que indiretamente está pressionada considerando-se os recursos divergidos da saúde pública para concluir suas decisões.

Palavras-chave: Direito à Saúde. Supremo Tribunal Federal. Paradoxo.

Abstract: The research has as its aim to identify if the STF performance on the right to health results in effectiveness or in symbolism. It was made by a theoretical research and an empirical investigation. The collect of data was centered in theoretical sociologist, with respective prominence given to the Niklas Luhmann´s Theory of Systems, which was used in the identification of legal rationality, social inclusion, complexity, contingence, justice, and the roles of Courts, the Legal and the Political Systems. In the theoretical reference, the conceptualization of the expression: “symbolic” is extremely rich. To a point that routinely semantic confusion is found; to avoid it, this work embraces the thesis developed by Marcelo Neves in his book: A Constitucionalização Simbólica (The Symbolic Constitutionalization), in which he develops a debate about the symbolism of constitutional norms. For the empirical research, by the methods of research, a documental investigation was made, collected from Brazilian Supreme Court´s leading cases. The research result arranged a paradox. It was found that the Brazilian Supreme Court, in a point of view restricted to the litigants, searches for an illusory effectiveness of the right to health, which is symbolic, inasmuch as the judge from a rationality exclusive adjudicatory, denying to see the issue, therefore, as an distributive issue, as a matter of distribution of wealth, which, in a macro perspective, causes the risk of corruption in the political system for forcing the public administration to distribute a wealth that, sometimes, does not even exist, as well as excluding most of the population, that does not have access to this Court or that indirectly are strained considering the diverged resources from the public health to accomplish its decisions.

Keywords: Right to Health. Brazilian Supreme Court. Paradox.

1 INTRODUCTION

This article is an excerpt from part of a doctoral research which has been made at PUC-SP Law College along with a doctoral exchange program at Macerata University – UNIMC, with a Capes (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) scholarship grant. It was researched the jurisprudence from the Federal Supreme Court in Brazil in order to verify if its rationality is symbolic or effective.

This work adopted a theoretical-empirical research. The literature review was performed based essentially on systemic authors, especially Nilkas Luhmann. The concepts of symbolism and effectiveness were obtained from Marcelo Neves’ work, “A Constitucionalização Simbólica” (The Symbolic Constitutionalization)[2]. The empirical material was collected from precedents of that Court, as well as from a survey of the expenses of the State to comply with judicial decisions on the topic.

The analyzed decisions on right to health were collected from the STF site[3], specifically in the jurisprudence link. For the web search, it was chosen expressions like: “right to health” and “separation of powers”, firstly in an isolated way and, then, together. This browsing process was used many times in a variety of completely different moments. When choosing the decisions which would be treated in details by the thesis, first, it was opted for two criteria: (i) objectively chosen, time; (ii) subjectively chosen, approach of the right to health in an explicit or implicit view of the separation of powers, since choosing the decision demanded from the observer mostly the implicit one.

At first, as an initial rule, it was opted for decisions published between 2009 and 2012, aiming an updated research. Next, not harming the time criterion, it was encompassed previously judged decisions which were identified as relevant to the understanding of the thinking followed by those being studied. Gradually, there was an increase of judged issues which passed the time constrained designed, in a way that the initial pattern was no longer the typical one. On the other hand, as to the methodological vies, the other initial research criterion was still preserved as an investigative principle: “right to health” and “separation of powers”.

Furthermore, even with the purpose of producing an objective research, it is undeniable that in the final selection of the analyzed samples, the collection was subjectively performed in a certain way. Thus, the researcher worked personally in his choices; however, it has always been focused on the critical treatment of the theme searched.

It was not excluded any specific group of procedural techniques from the collected samples, for example, Regulatory Appeal and Stay of Preliminary Order, since it was understood that maintaining them would enrich the research, resulting in a heterogeneous material from the procedural perspective of the judgments. Therefore, it was analyzed decisions of judgments of extraordinary appeals, regulatory appeals due to denial of extraordinary appeals, claims concerning suspension of preliminary injunctions, precautionary measure and ordinary appeals in injunctions.

After choosing this selection criterion, the final sample resulted in seventy one decisions, which were read, re-read, and finally meticulously studied one by one. The result is described next. It was selected twenty decisions from the universal sample which had a significant role in the research result. The main points of the judgments were transcribed in the footnotes.

2 DEVELOPMENT OF THE RESEARCH

A) Commonplaces in STF Micro Justice

As part of the result of the analysis, it was designed a map of the commonplaces seen in the STF (Brazilian Supreme Court) jurisprudence, which are: (i) the separation of powers which, according to this jurisprudence, is one of the pillars of modern democracy. However, concerning the collected material, sometimes the State used this premise in order to delegitimize the intervention of the Judiciary, when it is inactive and it does not accomplish its functions. But, different from the semantic previously granted, the Supreme Court nowadays sees this reasoning more properly as a political accommodation, thus it is not subject to opposing itself to the right to health by judicial performance, according to the terms decided in the Extraordinary Appeal n. 667.882/MG.

(ii) In many cases taken to Court, in fact, there are no appeals for the supply of a specific medication for the treatment of a rare illness. However, the Supreme Court decided for the obligation of its supply, mainly due to the fact that health is an indispensable asset. According to this decision, it is built the indispensability of the right to health in detriment of its concreteness, so that the Union brought Interlocutory Appeal n. 640722/SC against the denial of a special appeal, due to the TJSC (The Court of the State of Santa Catarina) decision, in which it was decided for the supply of the medication[4].

In the decision being studied, the right to health was considered inviolable. In the reasoning, many decisions were brought to light, in order to ratify its claim that STF has firmed a position in favor of preserving this right as an indispensable public right.

In the empirical material collected, (iii) the programmatic rules undertake a pattern completely different from the classic composition developed in the 60’s by José Afonso da Silva. In the decisions, it is assumed indeed that the right to health is provided in a programmatic rule. Nevertheless, its interpretation could not result in an inconsequent promise.

This statement is considered a divergent premise. Therefore, it is repeated as an axiom in a great number of decisions, for example, in judgments AI 662822/RS, AGR RE n. 393175/RS, and, as an example, following, there is a transcription of part of a judgment (RE n. 535145-MT):

[…] The Interpretation Of The Programatic Rule Can Not Trasform It In An Inconsequent Constitutional Promise. – The programmatic feature of Art 196 of the Magna Carta– which aims all the political entities forming the Brazilian federal organization, in an institutional plan – cannot become an inconsequent constitutional promise. Doing so, the government is risking defrauding collective fair expectations deposited on it, when illegitimately substituting the fulfillment of its undelayable duty, with an irresponsible act of government infidelity to what is asserted by the State fundamental law itself. […]

In another perspective, in the analyzed jurisprudence, (iv) the solidary responsibility of the public entities is uniform. It has always been routine of the Government the avoidance of the charge of supplying dignified health to the population using the excuse that it is not its responsibility. As an example, it is mentioned the suits filed by the states which in their defense claim that is an obligation of the Union.

Thus, there is no chance this subterfuge finds resonance in the present lines of studies adopted, due to the consistency of the solidarity thesis and until now, there is no communication from the highest court of justice in a different view. It is about a search for the effectivity as it can be concluded from the Extraordinary Appeal n. 607.385/SC filed in order to see the right to health accomplished when the medication is supplied. The decision was based on the thesis that health is a duty of all the federative entities. The party is responsible for choosing if it files suit against only one, two, or three of the entities (city, state, Union). In this specific case, the party just pleaded against the state of Santa Catarina. The judicial protection was granted[5].

In the rational myriad of the Supreme Court, it can be observed the rupture of obstacles recently considered insuperable by jurisprudence, in such a way that (v) new treatments which have not been inserted yet in ANVISA list can be performed, since they are proved to be need for the case. Therefore, what is acknowledgeable is that the evolution of medicine has been much faster than the state bureaucracy can follow.

Thus, the Judiciary and the State itself, with the aid of agencies or offices related to health issues, can recognize that in a specific case it is necessary to make use of a different medication or treatment which has not been practiced by the Brazilian state yet, but that is approved by the scientific community and that can bring benefits for the patient. For the same objective, treatments which are already available in the private health system and not practiced yet by the public one, for its high cost, or for its technological novelty, can be afforded by the State when necessary for the party’s treatment.

Moreover, (v) it was extended the supply of disposable diapers, based on the right to health, assuring the same constitutional status reserved to health to the ones who need it. In this decision, the Public Prosecution Office of the state of São Paulo filed a public interest civil action in order to oblige the city of São Paulo to provide disposable diapers to a teenager who had cerebral palsy, spastic tetraparesis and cognitive impairment. The plea was granted in the first judicial level and then sustained in the second level. Exactly for this reason, São Paulo City, filed an appeal that resulted in the decision which is being analyzed, based on the thesis that diapers would not be encompassed by the right to health. According to the appellant, it is not related to right to health. This thesis was denied. The appeal was declined. The interpretation which prevailed extended it to the right to health sustaining the previous decision which granted the benefit aimed[6]/[7].

In the dogmatic approach, (vi) the debate concerning the possibility or not to fulfill the right to health by the judiciary has always had the postulate of the reserve of possible as a persecutor. In summary, it means stating that the resources are scarce and the social needs are infinite. Thus, the Executive is responsible for analyzing what is more relevant. Therefore, the State-judge could not specifically interfere in these situations since there would not have resources; so, they would be scarce which forced the public administrator to realize the reserve of possible. This strong defense which was emphasized many times as an excuse, either in theory or by public administration, is completely discredited by the rationality of the STF. Due to the fact that, according to the Court, it would be dealing with constitutional values.

B) Adjudication and Symbolism

Historically, nothing can be stated about rights of second dimension, like the social ones, without mentioning the State role. Social rights are discussed as positive rights based on reaching common wellness and social justice. [8] One is implicit to the other. In fact, either the mentioned rights really exist, what would result in an obligation for the State to act, or simply do not exist and, in this second hypothesis since they are typified as a constitutional rule, it might rest qualifying it as a symbolic rule, at least concerning the theme at issue.

The social rights established by the legislation result in correlated state programs in light of other rights previously existing. Changing a constituted order is not an easy task, especially when this process must be performed without a drastic rupture from the previous order (the way it would happen in a revolution), through the implementation of public policies or the jurisdictional performance, when those are ineffective. This distributive process demands considerations different from the traditional adjudication process. It is required rationality when judging in a more refined way than the simplicity of right or wrong, so that it will be claimed from the judge a global analysis of the situation, which is not encompassed by the mentioned binomial (right or wrong), in order to approach an equanimous decision[9].

Due to this concept, there is a whole sense; a common wellness which will need to be divided in order to show each one’s share. To the judge, it remains, in the judicial process, the assignment to review this sharing criteria developed by the Public Administration, so that it would provoke a new sharing in order to better fulfill the law’s will[10].

Following this line of thought, it is good to remember that the subjective rights – as the right to health – are historical constructions. Becoming positive rights is an evolutive accomplishment of modern society. On the other hand, understanding it as a totally objective right, so to speak, placed and imposed to everything and everybody does not express an indication on its function in our present society, in a context of sustainable rationality in the long term. Also, for this reason, this perspective of analysis of the subjective rights, lacking any social balance, motivated Luhmann to label them as unfair rights[11].

Concerning the subjective public right to health as an individual indispensable right, the rationality of the Supreme Court is well defined as to its effectiveness in individual cases, which is almost unquestionable with the analysis of the precedents listed in the research. On the other hand, the issue of the right to health as a social public right is still incipient, being still used as a rhetoric to justify the individual aspect, but the global complex issue which is related to this problem, is far from any progress. Within this purpose, its social universalism is innocuous, it is left to observe if the parts will break, or not, the barriers imposed by the defensive jurisprudence of the STF resulting in an appealing judgment. However, the equality of each individual to receive their part in the right to health ends up degraded as if it did not exist[12].

The problem about judging cases of right to health is close to commutative and distributive justice. The jurists, greatly due to a theoretical traditional formation, generally do not accept facing issues of wealth distribution. Conversely, it is usual the resolution of commutative issues practically as an adjudication process. In these terms, courts are not prepared for a global analysis of the rights and appeals to make them effective, obviously because of the need to rethink the issue in an interdisciplinary way in harmony, for example, with economics and public administration. This difficulty in facing the issue under a distributive perspective can also be justified due to a cultural obstacle, result from a liberal education and, in Brazil, still a traditional social inheritance, since for many years only children from the elite studied law. This scenario influences the Court to be reticent in reasoning in a distributive way[13].

The same Court has already faced a similar situation of paradigm change when, in the Old Republic, it judged innumerous claims of suppression of the State activity concerning public health, made by the unpopular, at that time, Osvaldo Cruz. At that moment, liberal values so trendy at that time, like freedom itself, arouse intending to fight a great number of contagious illnesses result from a serious epidemic process faced by Brazil. The judgment was known as “The Vaccine Revolt”, judged by STF as RHC 2244[14].

Thus, it is stated that the jurisdictional positive process presumes, as undeniable consequences, the hermeneutics of the legal rule, or of the legal rules applied to the case, as well as of the facts declared by the parties. Initially, all of this in an individualized facet, and then the facts are led to the subsumption process. During this nonlinear process, the interpreter performs an intellectual process whose objective is to guide this reasoning, which is influenced by ideology.

Therefore, certain selectivity is inner to the mentioned intellectual interpretation procedure. Nevertheless, it is logical that at the time of the technical analysis of the rule, the peculiarities of the respective ruling species emerge, probably from the constitutional one, which is, according to Luhmann, the opening for the future when allowing that the juridical system foresees its own change through a new communication differed in the limits of self-referentiality of its respective binary[15].

Moreover, in the jurisprudence analyzed, it could be observed the guarantee of the right to health as an inalienable, indispensable asset, properly as a subjective public right. Clearly, as emphasized before, the Supreme Court produced such guarantee in its jurisprudence, mainly due to Mr Justice Celso de Melo’s votes. Not discrediting this historical conquer, it is being discussed that the recurrent practice of this commutative view by all of the Brazilian courts, surely will lead to a rupture of the system, conducing the State to a general bankruptcy for lack of resources. Also, it can be mentioned that when judging this way it is greatly reduced the reflexive power that should be offered by the Constitution[16].

By this perspective, it has to be aroused the thinking about the methodology of judging such a litigation, since it could be simply decided in favor of the aforementioned right, regardless its consequences or, in a different way, without considering the right, promoting a global analysis of the situation[17]. Moreover, nowadays, the function of the law is in its selective efficiency, in a continuous relationship with the society, paraphrasing Luhmann. The evolution of the law will depend greatly on how law itself reacts to society changes over time[18].

Specifically, still, the performances of the Supreme Court concerning the right to health, facing it as a distributive issue, is far from being ideal , fairly mentioning the public hearing headed by the President of the Court at that time, Mr Justice Gilmar Ferreira Mendes, when it was searched to understand the problem in a global way. Even if the judgments, since then, continue to be in a commutative way, the first step was taken. In this scenario, what is left is the pressure from those under jurisdiction against the STF through reiterated process claims under its power, which will gradually originate a new communication of the system, thus, reaching new selection processes, resulting in a decision different from the previous one.

The process of changing constitutional rules is originated from changes in the Constitution through constitutional amendments or from changes in the constitutional meaning granted by the time of the concretization of the constitutional rule. In this concretization process, Marcelo Neves points two ways of altering the Constitution, one of them is promoted by politics, which would act in a particular sense, based on a specific constitutional tool. Politics changed its way of acting based on an identical constitutional tool. Thus, it is said that the political system re-interpreted the aforementioned rule. On the other hand, the Judiciary interprets it when applying the Constitution to settle a conflict in a concrete case. However, in both situations, the altering process is influenced by interest, expectations and values involved at the time of the interpretation-application of the rule[19].

Concerning this issue, when the alteration of the constitutional rule is configured, it is adopted the systemic thesis that the evolution is designed from a new communication, whose content is not really meant to be something good. Hence, new rationality came and many others will as time passes by, in a continuous interface with the mentioned trichotomy, or maybe, who knows, the ones the future holds. Maybe, and for this reason, in the future it is reached the understanding that this judging attitude, with a collective optical, is related to a political acting and not to power seizing[20]. Also, in the constitutional classification, the right to health is inserted in a subdivision of the social rights, precisely rights of social security, which points universality and uniformity as principles.

In general, it is not possible to ratify that the Supreme Court judges a distributive right in an exclusive adjudicatory way, risking the representative statements of the Court – “It is important not to lose of sight that the subjective public right to health represents indispensable juridical prerogative guaranteed to people in general by the Constitution itself […]”[21] and “the interpretation of the programatic rule can not transform it in an inconsequent constitutional promise”[22] –, becoming symbolic in national context. As an example: think of your house infected by a huge number of ants. Many ants dominate the place. You cannot solve it. You hire experts. At the day set for the fumigation, the fumigation team has a strong and persuasive speech that your family will get rid of the ants. During their hard work, all the visible ants are killed. However, the next day, your dog dies poisoned and, one week later, the ants are back. What happened? It is a serious company. It was committed to the job! However, it faced the issue in an adjudicatory way, condemning the ants to death without thinking in a macro way, analyzing the whole (origin, consequences, etc.) in order to reach the objective in a global way. Therefore, even dedicating a great effort, it had a symbolic acting.

Obviously, encompassing the appropriate adaptation, the result of the research is very similar to the example above. While STF does not judge right to health considering a distributive view, sometimes it is much more generous in individual cases (claims) than in the collective processes, promoting the continuity of a gigantic exclusion of individuals from health. Thus, it ends up having a symbolic acting, as an “alibi”. It was done what could have been done. It was discussed with beautiful thesis – which undeniably consolidate a right in the juridical plan – but its non-resolution, by the distributive view, is represented as symbolic, despite the asset delivered to the claimers which obtained a favorable decision – a new elite[23].

c) Systemic Irritations Due to STF Acting

This “alibi” attitude of the STF contributes in a relevant way to an “irrational activism” scenario, whose consequences can also be measured by the data collected by the General Advocate of the Union, presented as follows, detached only from claims to the Union.

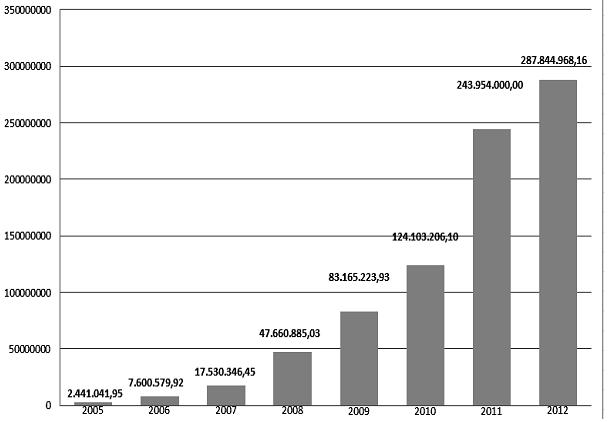

i) Significant increase of the medications purchased due to judicial cases. While it was spent R$2,441,041.95 in 2005, the purchase of medications in 2012 cost R$287, 844,968.16, as it can be seen in Figure 1, as follows.

Figure 1 – Development of the Union expenses with the purchase of medications complying court orders.

Source: General Advocate of the Union[24]

ii) Irrationality when distributing medications: 523 people resulted, judicially, in a cost of R$ 278, 094, 639, 71 to the Union. To this privileged, the Judiciary granted 18 new technologies, as it can be seen in Table 1, below:

Table 1: Name and cost of the most judicially supplied medications in disfavor of the Union:

| MEDICATION | TOTAL COST |

| BRENTUXIMAB VEDOTIN 50MG | R$ 309,515.87 |

| ERLOTINIB 150MG-TABLET | R$ 320,601.60 |

| SUNITINIB MALATE 50MG-CAPSULE | R$ 358,954.28 |

| TEMOZOLOMIDE 100MG-CAPSULE | R$ 455,033.60 |

| BOSENTAN 125MG – TABLET | R$ 708,900.60 |

| ALFA-1 ANTITRIPSIN – INTRAVENOUS SOLUTION | R$ 721,802.90 |

| PEGVISOMANT 10MG – INJECTABLE SOLUTION | R$ 881,650.99 |

| RITUXIMAB 500MG/50ML – INJECTABLE SOLUTION | R$ 1,108,400.70 |

| SORAFENIB TOSYLATE 200MG – TABLET | R$ 1,325,511.60 |

| MIGLUSTAT 100MG | R$ 1,769,571.00 |

| LARONIDASE 100U/ML – SOLUTION FOR INFUSION | R$ 10,597,226.21 |

| ALFALGLICOSIDASE – INJECTABLE SOLUTION | R$ 12,235,633.54 |

| ECULIZUMAB 300MG – SOLUTION FOR INFUSION | R$ 20,871,355.30 |

| TRASTUZUMAB 440MG – INJECTABLE SOLUTION | R$ 22,517,685.85 |

| AGALSIDASE BETA 35MG – SOLUTION FOR INFUSION | R$ 26,387,905.15 |

| AGALSIDASE ALFA 3,5MG – SOLUTION FOR INFUSION | R$ 40,676,764.09 |

| GALSULFASE 5MG/5ML – INJECTABLE | R$ 63,944,457.63 |

| IDURSULFASE 2MG/ML – INJECTABLE SOLUTION | R$ 73,713,668.80 |

| TOTAL | R$ 278,904,639.71 |

Source: General Advocate of the Union[25]

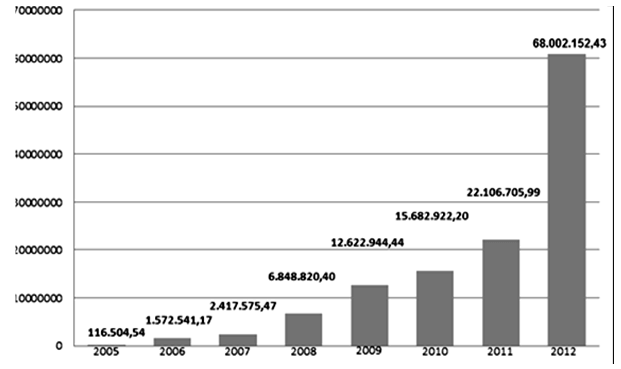

iii) Need of the Union to help states and municipalities financially because they could not fulfill the judicial orders. The amount increased from R$ 116,504.54, in 2005, to R$ 68,002,152.43, in 2012. In Figure 2, as follows, it is observed the evolution of the Union expense concerning this.

Figure 2 – Evolution of the Union expense in order to help states and municipalities

Source: General Advocate of the Union[26]

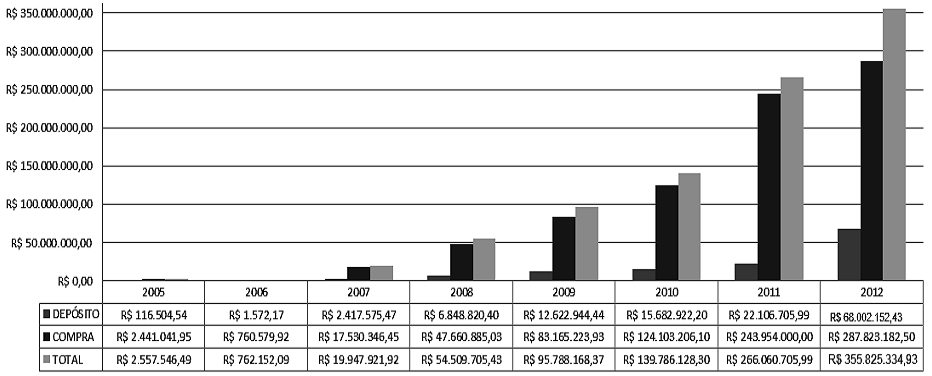

iv) In 2012, the Union spent more than R$ 350,000,000.00 with judicial deposit and the purchase of medications, while in 2005 the expense was R$2,557,546.49. As it can be seen in Figure 3, the evolution of the expense was extremely high.

Figure 3 – Evolution of the Union expense in order to fulfill judicial orders

Source: General Advocate of the Union[27].

The Union expenses, to fulfill the judicial decisions, are extremely high; however, the states face a worse situation, since in Brazil the distribution of the taxes collected benefits mainly the Union. In spite of the Union having more money, the amount of expense of the states in 2010 is alarming. The situation is: (i) São Paulo State spent R$ 700,000,000.00; (ii) Pernambuco State, fulfilling only 600 suits, had to pay R$40,000,000.00;(iii) Pará State spent R$913,073.81 in order to fulfill only 6 judicial claims; (iv) Minas Gerais declared removing money from public politics, promoted by the programs Farmácia de Minas e Saúde da Família (PSF) in order to obey the judicial orders[28].

Moreover, it is really emblematical the example from Campinas, a wealthy municipality, which had 16% of all its budget dedicated for purchasing medication redirected to fulfill 89 suits proposed in 2009. That is to say, 89 of the people under jurisdiction spent R$2,505,762.00, while more than a million inhabitants had to be pleased with what was left from the budget[29].

After observing the scenario described here, showing the increasing expense to fulfill claims to the Union, important questions arise: is health really effective in Brazil? Or is it closer to an “alibi” jurisdictional acting, whose effectiveness of the concrete case establishes the immunological system – the law – as a transmitter of more infection, instead of immunizing the society, as Luhmann said and, for this same reason, becoming a paradox that instead of protecting it is destroying it, as Guerra Filho teaches?[30].

D) Symbolic Role of the Supreme Court

The concept of the word “symbolic”, in the theoretical plan, is heterogeneous. The work adopts the one developed by Marcelo Neves in his book “A Constitucionalização Simbólica”. Precisely for the approach of the research, which has already been seen in the title of the research, the symbolic role of the STF, a priori, will be characterized when the “political-ideological” meaning prevails over its “juridical rationality”, materialized here by the jurisdictional role over the normative-juridical realization.

Hence, the symbolic decision would intend a social objective and not a fight for the effectiveness of the normative values. Being “alibi” understood as a tool, in fact, as it has been mentioned before, a “political-ideological” tool to justify the social pressures[31]. Nevertheless, it has a change of paradigm in the research, since Neves analyzed the symbolism of the Constitution and the research on its turn is centered in the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court[32].

Underlying Neves’ symbolic thinking there is a whole theoretical construction, based in Kindermann and Gusfield, with a clear systematization objective. In this path, it is confronted a classification of the symbolic laws in the following format: (i) rules as a confirmation of social values; (ii) rules as alibis; (iii) rules as future commitment. The first situation arises when there is a strong ideological polarization conducted obviously by antagonistic and confrontational social groups. The rivalry is taken to the parliament in order to have a winning side when voting a specific law project. In some situations, it is indeed a religious litigious, as it happened between Protestants and Catholics in the Prohibition in the United States of America. The approval of the law prohibiting selling alcohol was a great victory for native people (Protestants) against immigrants (Catholics), regardless the social effectiveness of the rule.[33].

The legislation as a confirmation of social values is the first example of legislation demonstrated by Marcelo Neves. And this is really curious, since it seems unconventional that social movements please themselves with the legislative conquer and do not worry with the realization of the values granted. Neves lists examples as the American Prohibition, when Protestants supporting the law fought a political battle against Catholics who opposed its approval. Based on Gusfield, Neves advocates that Protestants aimed the approval of the law much more as a battle of forces than as the real accomplishment of its value[34]. Perhaps, from a different point of view, it was not indifference for the social effectiveness; however, this one would be in a second plan since in the first place it would be the political victory, in a total defeat of the other social group..

The second hypothesis pointed by Neves concerns the alibi-legislation. In this one, the legislator had the intent to conquer the public opinion. Often, it is demanded from the parliament attitudes, even immediate attitudes, to solve social problems, regardless the kind of problem, even if the ruling production, as in a magic trick, cannot solve it. This expression: “alibi-legislation”, as aforementioned, was conceived by Kindermann. It encompasses situations like the ones in voting processes, when politics promote their acts as a way to gain electors or to keep the same ones from the previous voting.[35].

Yet, concerning symbolism, Marcelo Neves, based on Freud and Gusfield, each one in his own theoretical context, develops a thinking about the latent and prominent meaning of the juridical rules, entangling in a deep concept about symbolic legislation, which would be by another vernacular , a precept holding the illusion of a prominent function. Editing it did not really intend that the values settled in it would become effective. It was aimed another goal in a latent – hidden- way, for example, from a political-ideological origin[36].

The social charge against the political system is a communicative reaction. Concerning the legislative production, new laws will be voted and approved due to social claims. It is curious indeed that in some situations, legislators are aware of the ineffectiveness of this new law. Although it will be socially approved, it will have a few or none coercive power. In spite of this awareness, since it is necessary, it is created an “alibi” as a motto to reinforce momentarily the popular trust in the government. Nevertheless, the recurrent practice of such a tool can generate a reversal effect, strengthening the disbelief concerning politicians[37].

Generally, the idea of postponing the solution of a social problem is related to the seriousness of this problem. Since it is a serious problem, having a difficult solution, it is searched to postpone it through the creation of palliative actions. As an example, there are in some parts of Brazil, actual concentrations of misery, a situation originated from a strong negative social-economic reality, which is not possible to be solved in short term. Therefore, the Brazilian government designed many different aid plans, labeled as “bolsas” (conditional cash transfers), which, as mentioned before, lessen but do not solve the situation. Without disbelieving this analysis, the idea here is a different one: the parliament sees the need of answering the voters; however, there is no consensus concerning the actions that must be taken to solve the issue. Thus, due to the immediate need of an answer, it is reached an agreement in producing a certain rule, which is known, will not solve the situation. Nevertheless, since there is no agreement on the actions need, it is edited a law properly as a problem postponing. It is a way to give an answer (still sterile) to the society’s claims[38].

3 CONCLUSION

Regarding the results of the research, as the empirical data collection showed, both initial hypothesis – effective acting or symbolic acting- when isolated observed, were considered inconclusive, inconsistent and, specially, too much simple to describe such a complex environment. Therefore, the original proposal of this thesis had to be open to a less nominalistic, positive and labeling description , in order to provide a more contextual, analytical and sensitive result.

In fact, it is undeniable that it really exists in the Supreme Court a juridical rationality definition concerning the realization of the right to health, when the observation focus the micro justice view – justice between the parties – which, however, reaches a symbolic acting just when it does nothing relating the innumerous people under jurisdiction who had the right to health dishonored and could not make their claims reach the Court.

Micro justice, in this case, connects to new elite: the one who possesses technical tools to reach STF. And it dives deeply in the alibi-symbolism when denying access to distributive justice and continuing to face the situation only by the adjudicatory propensity, ratifying the assertion that the judge is not in charge of worrying about the public budget and, much less, to let minor interests, like the lack of resources, harm exactly the social rights which mean not more than the search for economic equality. Markedly, because if it is true that for analyzing the meaning around STF, it must be considered the gigantic increase in the complexity. Also, it is not less truth that if the Court when judging does not consider this same complexity to form its rationality, it will gradually develop a symbolic meaning, in harmony with the idea of an alibi concerning its inability to maintain expectations over the time.

The Supreme Court symbolic acting is identified when it denies to observe the observers (the jurisdictional acting of other judges) in order to, this way, plays the role of being the “second order observer”. Thus, it should (i) analyze the social complexity generated by the judicial processes interfaced with the other social subsystems with the objective to regulate the theoretical consistency of the decisions concerning social adequacy, taking, if necessary, measures of reviewing jurisprudence and even proposing editing regulation measures of the state activity nationally, like the edition of binding precedents and/or (ii) judging collective processes more willingly.

REFERENCES

ADVOCACIA GERAL DA UNIÃO. Consultoria Jurídica/Ministério da Saúde. Intervenção judicial na saúde pública. Panorama no âmbito da Justiça Federal e apontamentos na seara das Justiças Estaduais. [s.d.] Disponível em: <http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/portalsaude/arquivos/pdf/2013/Jun/14/Panoramadajudicializacao_2012_modificadoemjunhode2013.pdf>. Acesso em: 18 out. 2013.

BANDEIRA DE MELLO, Celso Antônio. Eficácia das normas constitucionais e direitos sociais. São Paulo: Malheiros, 2009.

BARROSO, Luís Roberto. Constituição, democracia e supremacia judicial: direito e política no Brasil contemporâneo. In: LEITE, George Salomão; SALET, Ingo Wolfgang (Orgs.). Jurisdição constitucional, democracia e direitos fundamentais. Salvador: JusPodivm, 2012. p. 363-406.

CAMPILONGO, Celso Fernandes. Governo representativo “versus” governo dos juízes: A “autopoiese” dos sistemas político e jurídico. Belém: UFPA, 1998.

_____. O direito na sociedade complexa. São Paulo: Max Limonad, 2000b.

_____. Política, sistema jurídico e decisão judicial. São Paulo: Max Limonad, 2002.

FEBRRAJO, Alberto. Legitimazione e teoria dei sistemi. In: TREVES, Renato (Org.). Diritto e legitimazione. Milano: Franco Angeli, 1985. p. 21-35.

FINATTI, Deise Barbieri; VECHINI, Priscila Garbin. O perfil dos gastos destinados ao cumprimento de determinações judiciais no Município de Campinas. XXIV Congresso de Secretários Municipais de Saúde do Estado de São Paulo. Anais… Campinas, São Paulo, 2009. Disponível em: <http://2009.campinas.sp.gov.br/saude/biblioteca/XXIV_Congresso_de_Secretarios_Municipais_de_Saude_do_Estado_SP/Complexidadedaatencaobasica/O_Perfil_dos_gastos_Deise.pdf>. Acesso em: 22 out. 2013.

FOERSTER, Heinz von. Sistemi che osservano. Traduzione Bernardo Draghi. Roma: Casa Editrice Astrolabio, 1987.

GUERRA FILHO, Willis Santiago. Teoria da ciência jurídica. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2001.

_____. Luhmann and Derrida: Immunology and Autopoiesis. In: LA COUR, Anders; PHILIPPO-POULOS-MIHALOPOULOS, Andreas (Eds.). Luhmann Observed: Radical Theoretical Encounters. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2012.

LOPES, José Reinaldo de Lima. 4. Crise da norma jurídica e a reforma do judiciário. In: FARIA, José Eduardo (Org.). Direitos humanos, direitos sociais e justiça. 4. tir. São Paulo: Malheiros, 2005. p. 68-93.

_____. Direitos sociais. Teoria e prática. São Paulo: Método, 2006.

LUHMANN, Niklas. Le norme nella prospettiva sociológica. In: A cura di GIASANTI, A; POCAR, V. La teoria funzionale del diritto. Milano: Edizioni UNICOPOLI, 1981. p. 51-85.

_____. Teoria politica nello Stato del benessere. A cura di SUTTER, Raffaella. Milano: Franco Angeli, 1983b.

_____. La differerenziazione del diritto. A cura di DE GIORGI, Rafaelle. Milano: Mulino, 1990b.

_____. Poder. Traducción Luz Mónica Talbot. Barcelona: Anthropos, 1995a.

_____. Procedimenti giuridici e legittimazione sociale. A cura di FEBBRAJO, Alberto. Milano: Giuffré, 1995b.

_____. Introducción a la teoría de sistemas. Versão espanhola Javier Torres Nafarrate. Mexico: Universidad Ibero Americana, 1996a.

_____. La costituizione come acquizione evolutiva. In: A cura di ZAGREBELSKY, Gustavo; PORTINARO, Pier Paolo; LUTHER, Jörger. Il futuro della costituzione. Torino: Giulio Einaudi editore, 1996b.

_____. EI derecho de Ia sociedad. Traducción Javier Nafarrate Torres. 2. ed. Mexico: Universidad Iberoamericana, 2005.

MANSILLA, Darío Rodríguez; NAFARRATE, Javier Torres. Introducción a la teoria dela sociedade de Niklas Luhmann. Mexico: Herder, 2008.

NEVES, Marcelo da Costa Pinto. Costituzionalizzazione simbólica e decostituzionalizzazione di fatto. Traduzione Michele Carducci. Lecce: Pensa, 2004.

_____. A força simbólica dos direitos humanos. Revista Eletrônica de Direito de Estado. Salvador, n. 4, p. 1-35, outubro/novembro/dezembro, 2005. Disponível em: <http://www.direitodoestado. com.br>. Acesso em: 25 out. 2011.

_____. A constitucionalização simbólica. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2007.

PARSONS, Talcott. La prospettiva sociologica della professione legale. In: A cura di GIASANTI, A; POCAR, V. La teoria funzionale del diritto. Milano: UNICOPOLI, 1981. p. 84-102.

SARMENTO, Daniel. Constitucionalismo: trajetória histórica e dilemas contemporâneos. In: LEITE, George Salomão; SARLET, Ingo Wolfgang (Orgs.). Jurisdição constitucional, democracia e direitos fundamentais. Salvador: JusPodivm, 2012. p. 87-124.

SILVA, José Afonso da. Curso de direito constitucional positivo. 29. ed. São Paulo: Malheiros, 2007

VILANOVA, Lourival. Causalidade e relação no direito. 4. ed. rev. atual. e ampli. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 2000..

Notas de Rodapé

[1] Full Professor at UNITOLEDO, Araçatuba – SP – Brazil.

[2] São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2007.

[3] STF’s site : .

[4] BRASIL. Supremo Tribunal Federal. Recurso Extraordinário com Agravo (Interlocutory Appeal) n. 640722/SC. Rapporteur: Mr Justice Ricardo Lewandoski. Plaintiff: União. Defendant: Ministério Público Federal. Witness: Estado de Santa Catarina. Witness: Município de Videira. Brasília, DF. Judged in: 05.24.2011. Published in: 05.30.2011. Retrieved October 16, 2013, from <http://stf.jusbrasil.com.br/jurisprudencia/22936567/recurso-extraordinario-com-agravo-are-640722-sc-stf>. Part of the same judgment: p. 1: “1. The Federal Constitution precisely elects health as a right of everybody and a duty of the State. (Art 196). Then it can be concluded: it is the State’s obligation, in a generic sense (Country, State, Municipality), to guarantee to needy people the access to the medication necessary to heal their illnesses, specially the most serious ones”. Part of the same judgment, p. 1: “2. The public law subjective to health represents an indispensable juridical prerogative guaranteed to people in general by the Constitution itself. (Art 196)”. Part of the same judgment, p. 1: “3. The Government, regardless the sphere of acting in the federal organizational plan, cannot demonstrate indifference to the population’s health problem, risking having, even due to omission, a serious unconstitutional attitude”.

[5] BRASIL. Superior Tribunal Federal.Agravo em Recurso Extraordinário (Extraordinary Appeal) n. 607.385/SC. Rapporteur: Mrs Justice Cármen Lúcia. Plaintiff: Estado de Santa Catarina. Defendant: Elisa Meira Fernandes. Brasília, DF. Judged in 04.19.2011. Published in 05.12.2011. Retrieved October 16, 2013, from <(http://stf.jus.br/portal/diarioJustica/verDiarioProcesso.asp?NumDj=88&dataPublicacaoDj=12/05/2011&incidente=3814696&codCapitulo=6&numMateria=68&codMateria=3>. Part of the same judgment, p. 2: “The author-party filed a suit against the State of Santa Catarina aiming the supply of an essential medication for the treatment of an illness. According to the recent jurisprudence of STJ, the three federative entities are jointly responsible for fulfilling the right to health, as it can be seen from the decisions below: […] As it is a solidary obligation, it is possible to demand it from one or all the federative entities. The author-party is in charge of choosing it. Regard this case mentioned above, the author-party opted to sue the State of Santa Catarina, so this defendant, and only this one, must be part of the passive side of the claim. (Emphasis added)”. Also, regard the guarantee of the solidarity to the right to health among public entities, see BRASIL. Supremo Tribunal Federal. Recurso Extraordinário (Extraordinary Appeal) n. 584652/RJ. Rapporteur: Mr Justice Cezar Peluso. Plaintiff: Union. Defendant: Produtos Veterinários Manguinhos LTDA. Brasília, DF. Judged in: 08.07.2008. Published in: 09.02.2008. Retrieved October 16, 2013, from <http://stf.jusbrasil.com.br/jurisprudencia/14771245/recurso-extraordinario-re-584652-rj-stf> Part of the same judgment, p. 2: “If this were not so, the State refusal to supply medication risks the health of a patient in need and it represents disrespect to Art 196 of the Federal Constitution, which states that health is a right of everybody and a duty of the State. This constitutional rule aims all the political entities which are part of the federative organization of Brazil”.

[6] BRASIL. Supremo Tribunal Federal. Agravo em Recurso Extraordinário n. 646.235/SP. Rapporteur: Mrs Justice Cármen Lúcia. Plaintiff: Município de São Paulo. Defendant: Ministério Público do Estado de São Paulo. Brasília, DF. Judged in 08.01.2011. Published in 08.05.2011. Retrieved October 16, 2013, from <http://stf.jus.br/portal/jurisprudencia/listarJurisprudencia.asp?s1=%28ARE%24%2ESCLA%2E+E+646235%2ENUME%2E%29&base=baseMonocraticas&url=http://tinyurl.com/mcc3do2> Part of the judgment, p. 2: “The extraordinary appeal was fulfilledagainst the following judgment of Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo: ‘ Public Civil Appeal – Required review and voluntary resource by São Paulo municipality – Public Civil Appeal – Fundament to obligate the municipality to furnish disposable diapers to a teenager who had cerebral palsy, spastic tetraparesis and cognitive impairment – Illegitimacy preliminaries eliminated – The whole protection , according to the reasoning of articles 1º and 11, §2º, Law 8.069/90 (ECA – Child and Adolescent Statute), of the deprived teenager, justifies the free supply of the item, according to medical prescription – Inadequacy of arguments which see in the Judiciary acting an inadequate intrusion in the Executive when acknowledging children’s priority rights – Suitable fine according to Art 213, §2º (ECA), applied reasonably. Appeals denied’”. (p 209)

[7] Part of the same judgment, p. 2: “It asserts that ‘there is no connection between diapers and the right to health and life’ and that ‘since it is not a medication, there is no sense in mentioning subjective public law directly from the Federal Constitution’ (p. 328). (Emphasis added)”.

[8] TAVARES, André Ramos. Curso de direito constitucional. 6. ed. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2008. p. 769 e 772.

[9] LOPES, 2006, p. 233-235. See p. 237 in the same literature: “Judging from these features it is no surprise that it is still difficult a more detailed discussion on social rights in the jurists works and that they leave the ‘common place’ of the ‘dignity of the human being’, kind of juridical hocus pocus of a society, in which the moral discussion – where the concept of human dignity itself comes from – is not public”. Also, from this literature, p. 291: “[The significant point is always this one: may present rights of individual subjects be qualified in the name of future rights of other subjects, among them included the ‘harmed’ rights? In other words, is it possible to redistribute the rights?”.

[10] LOPES, 2006, p. 142: “Distribution means sharing something ordinary. Distributing means taking something which is a whole and dividing it”. Also, see Neves, 2005, p. 8, on social rights as collective assets.

[11] LUHMANN, 1990b, p. 299, 305.

[12] LOPES, 2006, pp. 256-259. On page 280: “[…] Law was recognized as a tool of social engineering. So it was necessary to overcome the liberal tradition of (a) non-intervening in the contracts, and (b) rigorous division of the three spheres, specially isolating the Legislative and the Judiciary”.

[13] See BARROSO, 2012, p. 375, on the judges’ institutional capability in the analysis of the systemic effects of their decision: “[…], the constitutional doctrine has explored two ideas aiming the judicial influence: the one related to institutional capability and the one on systemic effects. Institutional capability encompasses the determination of which sphere is more able to produce the best decision on a specific issue. […] Also, the risk of unpredictable and undesirable systemic effects may recommend an attitude of caution and reference from the Judiciary. The judge, due to vocation and training, will be often prepared to perform the concrete case justice, micro justice, many times without conditions to evaluate the impact of the decisions over an economic segment or over a public service offer”.

[14] BRASIL. Supremo Tribunal Federal. RHC 2244. Rapporteur: Mr Justice Hermínio Espírito Santo. Judged in 31.01.1905, Published in 02.03.1905. Retrieved October 9, 2013, from http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/cms/verTexto.asp?servico=sobreStfConhecaStfJulgamentoHistorico&pagina=STFPaginaPrincipal1 “The Vaccine Revolt was a movement which happened from Nov. 10 to 16, 1904, in Rio de Janeiro City , against the obliged vaccine campaign imposed by the federal government”. On this issue see LOPES, José Reinaldo de Lima; QUEIROZ; Rafael Mafei Rabelo Queiroz; ACCA, Thiago dos Santos. Curso de História do Direito. São Paulo: Método, 2006. p. 489. Likewise, it can be analyzed the beginning of the historical process of constitutionality control , notably the French senate in the mentioned control in 1799. However, since it was a political organ, which was not committed to technique either, it was practically not useful at that moment, inclusive due to Napoleão Bonaparte’s actions. Nevertheless, a worthwhile result, historically seen, that generated some tension by that time, was the performance of the American Supreme Court in the notorious case Marbury versus Madison in 1803, when at the first time it was declared the unconstitutionality of a law. Additionally, the outlines of an American law on unconstitutionality were adopted, and a great part of the modern constitutionalism was absorbed from it.

[15] LUHMANN, 1996b, p. 100. On future rights as an opening for the future, see NEVES, 2005, p. 8.

[16] NEVES, 2007, p. 69-74, 95.

[17] LOPES, 2007, p. 137, 155. In a text approaching the Constitution as an evolutive acquisition of the modern society, Luhmann reports that the Constitution itself must break the circle of self-referentiality in order to translate symmetry into asymmetry. Cf. LUHMANN, 1996b, p. 97.

[18] LUHMANN, 1983b, p. 116.

[19] NEVES, 2004, p. 13, 15-17.

[20] Concerning the judicial acting as a political complement emphasizing commutative judgments, see LOPES, 2007, p. 181. On distributive and commutative justice, see LOPES, 2006, pp. 282-283. In order to analyze some distributive cases in Brazil focusing consumer’s law, see LOPES, 2006, p. 141-161.

[21] BRASIL. Supremo Tribunal Federal. Agravo Regimental em Recurso Extraordinário (Internal Interlocutory Appeal) n. 271.286-8/RS. Rapporteur: Mr Justice Celso de Mello. Appellant: Município de Porto Alegre. Appellee: Cândida Silveira Saibert. Appellee: Dina Rosa Vieira. Brasília, DF. Judged in: 11.24.2000. Excerpt: p. 1.419. Retrieved October 24, 2013, from <http://redir.stf.jus.br/paginadorpub/paginador.jsp?docTP=AC&docID=335538>.

[22] BRASIL. Supremo Tribunal Federal. Agravo Regimental em Recurso Extraordinário (Internal Interlocutory Appeal) n. 393.175-O/RS. Rapporteur: Mr Justice Celso de Mello. Appellant: Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Appellee: Luiz Marcelo Dias et al. Brasília, DF. Published in DJ in 02.02.2007. Excerpt: p 1.524. Retrieved October 24, 2013, from <http://redir.stf.jus.br/paginadorpub/paginador.jsp?docTP=AC&docID=402582>.

[23] NEVES, 2007, p. 95: “Even though from the juridical view the symbolic constitution is seen negatively due to the lack of ruling concretization of the constitutional text, it also has a positive aspect, since the constitutional activity and language play an important ideological-political role. Accordingly, it demands a different treatment of the traditional approaches regarding ‘inefficacy’ or ‘non-realization’ of the constitutional rules”. Also, see, NEVES, 2007, p. 96: “Concerning symbolic constitutionalization, the constitutional activity and the emission of the constitutional text are not followed by a general juridical ruling, an extensive ruling concretization of the constitutional text”.

[24] ADVOCACIA GERAL DA UNIÃO (General Advocate of the Union). Consultoria Jurídica/Ministério da Saúde. Intervenção judicial na saúde pública. Panorama no âmbito da Justiça Federal e apontamentos na seara das Justiças Estaduais. [n.d.] Retrieved October 18, 2013, from <http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/portalsaude/arquivos/pdf/2013/Jun/14/Panoramadajudicializacao_2012_modificadoemjunhode2013.pdf>.

[25] ADVOCACIA GERAL DA UNIÃO (General Advocate of the Union). Consultoria Jurídica/Ministério da Saúde. Intervenção judicial na saúde pública. Panorama no âmbito da Justiça Federal e apontamentos na seara das Justiças Estaduais. [n.d.] Retrieved October 18, 2013, from <http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/portalsaude/arquivos/pdf/2013/Jun/14/Panoramadajudicializacao_2012_modificadoemjunhode2013.pdf>.

[26] ADVOCACIA GERAL DA UNIÃO (General Advocate of the Union). Consultoria Jurídica/Ministério da Saúde. Intervenção judicial na saúde pública. Panorama no âmbito da Justiça Federal e apontamentos na seara das Justiças Estaduais. [n.d.] Retrieved October 18, 2013, from <http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/portalsaude/arquivos/pdf/2013/Jun/14/Panoramadajudicializacao_2012_modificadoemjunhode2013.pdf>.

[27] ADVOCACIA GERAL DA UNIÃO (General Advocate of the Union). Consultoria Jurídica/Ministério da Saúde. Intervenção judicial na saúde pública. Panorama no âmbito da Justiça Federal e apontamentos na seara das Justiças Estaduais. [n.d.] Retrieved October 18, 2013, from <http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/portalsaude/arquivos/pdf/2013/Jun/14/Panoramadajudicializacao _2012_modificadoemjunhode2013.pdf>.

[28] ADVOCACIA GERAL DA UNIÃO (General Advocate of the Union). Consultoria Jurídica/Ministério da Saúde. Intervenção judicial na saúde pública. Panorama no âmbito da Justiça Federal e apontamentos na seara das Justiças Estaduais. [n.d.] Retrieved October 18, 2013, from <http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/portalsaude/arquivos/pdf/2013/Jun/14/Panoramadajudicializacao_2012_modificadoemjunhode2013.pdf>

[29] FINATTI, Deise Barbieri; VECHINI, Priscila Garbin. O perfil dos gastos destinados ao cumprimento de determinações judiciais no Município de Campinas. XXIV Congresso de Secretários Municipais de Saúde do Estado de São Paulo. Anais… Campinas, São Paulo, 2009. Retrieved October 22, 2013, from <http://2009.campinas.sp.gov.br/saude/biblioteca/ XXIV_Congresso_de_Secretarios_Municipais_de_Saude_do_Estado_SP/Complexidadedaatencaobasica/O_Perfil_dos_ gastos_Deise.pdf>.

[30] LUHMANN, 2005, 219; GUERRA FILHO, 2001, p. 186-187; LUHMANN, 1977, p. 115. GUERRA FILHO, 2012, p. 3.

[31] NEVES, 2007, p. 1-3. Still, concerning Marcelo Neves’ work, named “A Constitucionalização Simbólica”, it is emphasized that it was through its reading that Niklas Luhmann rethought the idea of autopoiesis in order to recognize alopoiesis.

[32] NEVES, 2007, p. 19, mostly p. 30-31: “[…] Nevertheless, the concept of symbolic legislation must refer more extensively to the act of text producing and to the text produced, revealing that the political meaning of both prevails excessively over the apparent normative-juridical meaning. The deotontic-juridical reference of action and text to reality becomes secondary, becoming relevant to the political-valuing or ‘political-ideological’ reference”. Also, see NEVES, Marcelo da Costa Pinto. Costituzionalizzazione simbólica e decostituzionalizzazione di fatto. Traduzione Michele Carducci. Lecce: Pensa, 2004. p. 29, 32.

[33] NEVES, 2007, p. 33-36.

[34] NEVES, 2007, p. 33-34. The author mentions two more examples about situations on confirming social values, both in Europe; one concerning abortion, the other on foreigner’s legislation. Cf. p 34-35.

[35] NEVES, 2007, p. 36-37.

[36] NEVES, 2007, p. 22-33, mainly p. 33: “Kidermann proposed a tricothomic model for the tipology of the symbolic legislation, whose systematicity makes it fructiferous: “ The content proposed a tricotomic model for the tipology of the symbolic legislation whose systematicity makes it theoretically frutiferous: ‘Content of the symbolic legislation can be : a) confirming social values, b) demonstrate the State ability to act, and c) postpone the solution of social conflicts through dilatory commitments’”. As the transcription presents, Neves, based on Kindermann, claimed a triple-divided model of the latent intuition of this symbolic legislation: (i) social values confirmation, (ii) álibi-legislation, (iii) legislation as a dilatory commitment. Cf. NEVES, 2004, p. 27-28.

[37] NEVES, 2007, p. 36-41, it is literally mentioned, p. 33: “[…] However, when the new legislation is just one more attempt to present the State as an entity identified with the values or goals strongly protected by it, without any new result regard the normative concretization, clearly we will be facing a case of symbolic legislation”. Cf. NEVES, 2004, p. 28-29.

[38]nbsp; NEVES, 2007, p. 41-42.